Blueprint of a Bottling - Part 1

Everything, Everywhere, All at Once

Packaging can be theater, it can create a story ~ Steve Jobs

Genesis

It all started 18 months ago when we picked 1,632 pounds of Cabernet Sauvignon grapes from a tiny vineyard on Carriger Road on the west side of Sonoma, another 512 pounds of Cab from an old vine vineyard up in Dry Creek, 1,894 pounds of Syrah from a small Sonoma vineyard beyond Aqua Caliente, 1,210 pounds of Zinfandel field-picked with 804 pounds of Petite Sirah from a sandy vineyard in the Sacramento River Delta down by Oakley, and 1,087 pounds of Malbec from a mountain vineyard up on Bennet Valley Road. I would then go through a year and a half of worry and wonderment, willing all that wine into six barrels of what I would eventually call my Requisite Red Blend, and three barrels of my Eclipse Malbec.

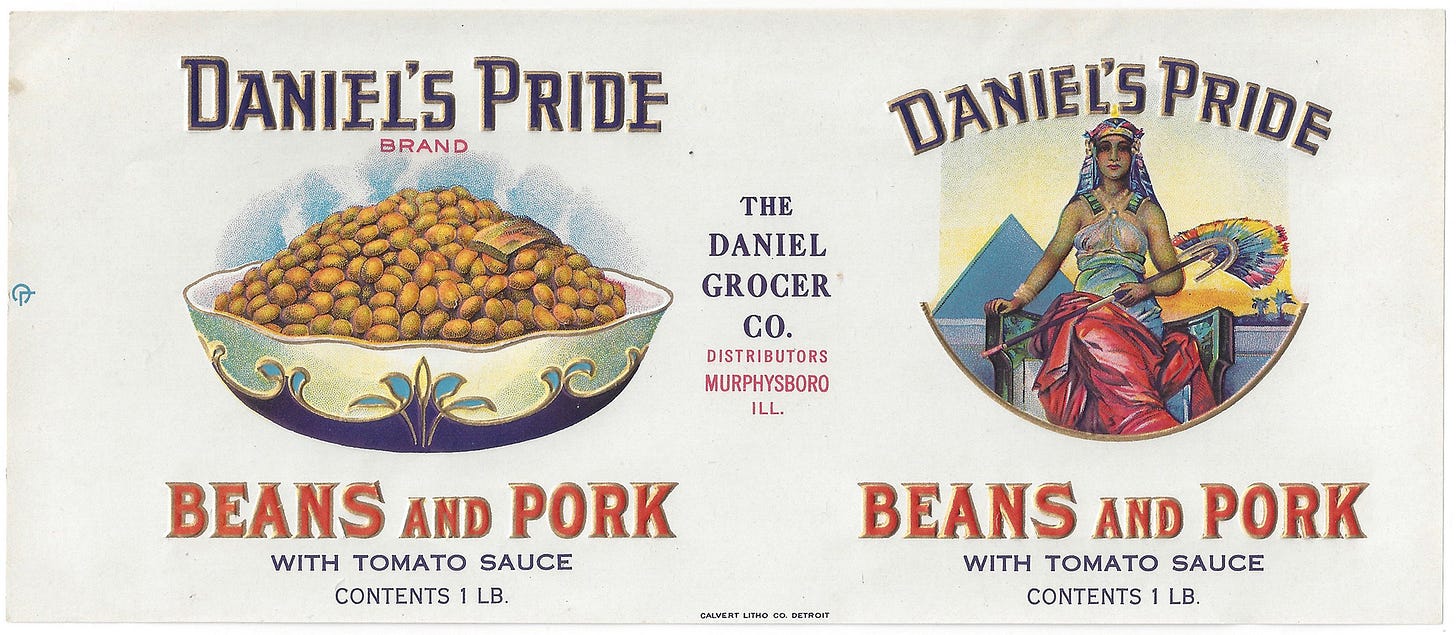

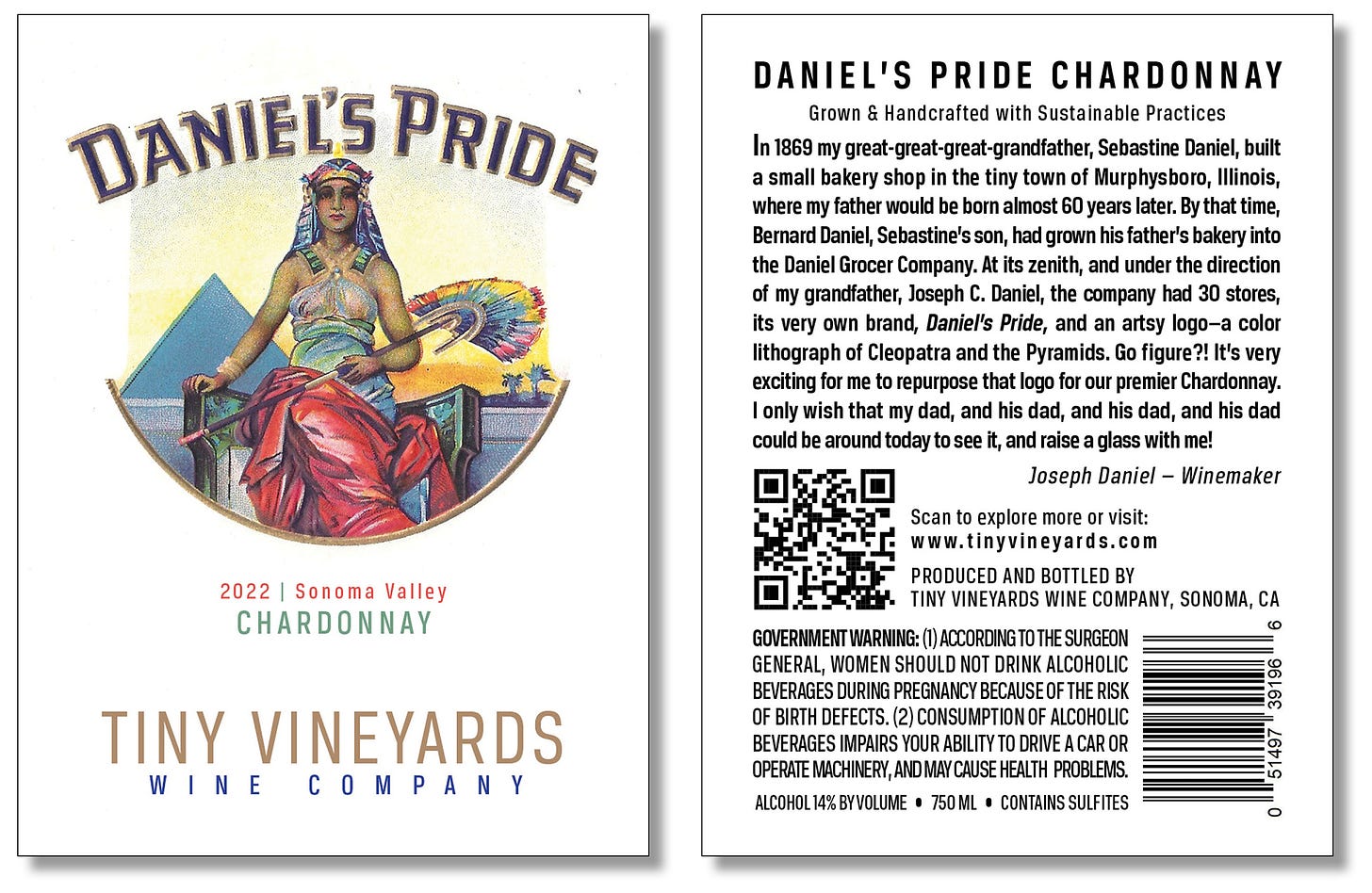

Twelve months later I would add 1,852 pounds, two barrels worth, of Chardonnay grapes from a tiny vineyard on the other side of town, because I thought I should have a white wine amongst my first offerings. And since whites don’t take anywhere near as long to make as reds, I could pick it a year later and still add it to my inaugural release. I even repurposed a brand and a label for it, Daniel’s Pride, which had been in my family of grocers for over 100 years.

And now, in just 12 days, I’ll finish prepping these three wines a final time and bottle them all, applying labels, inserting corks, and spinning on capsules. Then I’ll put them asleep again for another six months in a big commercial wine storage facility—an industrial cave, if you will, with just the right temperature, lack of light and lack of movement, to compel the wines to regather, to emulsify and soften, polymerize tannins, recompose colloidal structure and seek equilibrium in their mysterious flavor and aromatic compounds. Only then will I release them.

So how do I get from here to there?

Bottles

Last week I wrote about the Unified Symposium, usually referred to as just the “Unified.” That’s really where I began in earnest to build a package for my wine. I wanted to meet and talk with multiple suppliers for everything I would need. Bottles—or glass as they’re referred to generically in the industry—were my foremost concern, mainly because there had been a growing glass shortage since the pandemic and prices had gone through the roof. International freight delays, labor shortages and higher container costs had also contributed to supply chain challenges and trying to find quality glass in traditional 750ml, antique green for under $10 to $12 a case had become a challenge.

I was also very concerned about using overweight premium bottles considering the excess material and carbon footprint they represented (just about all the glass used for wine bottles is manufactured overseas), and the often deal-breaker shipping costs they further incurred when sending them, full of wine, back out to customers. I know, I know, there is a preconceived notion that the heavier the bottle, the higher will be the quality of the wine inside. But misconceptions like that have to change if we hope to survive into a sustainable future. I was looking for what are known as Eco bottles, something that weighed between 350 to 550 grams (454 grams is a pound), as opposed to Luxury bottles that can weigh between 800 to 1,200 grams.

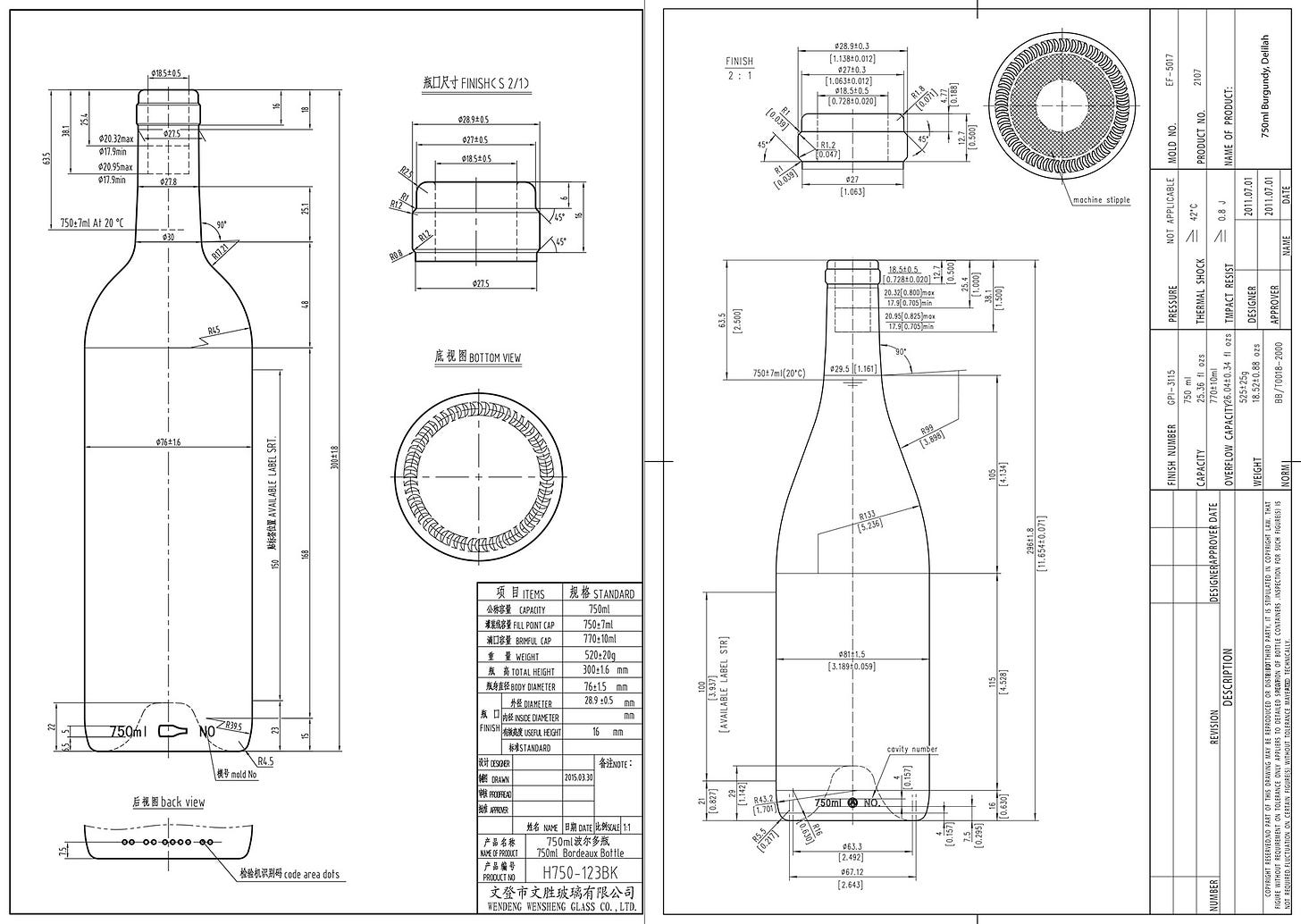

To find my perfect glass I visited five companies at the Unified—Encore Glass, West Coast Bottles, Saxxo, Berlin Packaging and Tricor Braun. I asked to see both Bordeaux and Burgundy style Eco bottles in antique green. All those companies had versions of what I was looking for in stock, which was a really good sign, so I requested price quotes, tech drawings and sample bottles so I could compare the dozens of different interpretations of antique green, make sure my labels, corks and capsules would fit, and be able to heft each bottle to feel it’s empty weight.

A few days later the samples started to arrive and the tech drawings and price quotes flooded my inbox. I eventually selected a Bordeaux bottle (straight sided with high shoulders) from Tricor Braun and a Burgundy bottle (low sweeping neck) from Berlin Packaging. How did I arrive at that selection? I preferred the darker green of each of them to the other samples, they each weighed on the higher end of the Eco range so they still had a bit of heft, and the price for each was the lowest I was quoted from anyone. The Bordeaux bottles were $7.96 a case and the Burgundy (normally a bit higher than Bordeaux) were $10.00 a case.

The Burgundy bottles get delivered to Magnolia (my winery) tomorrow, the Bordeaux bottles on Wednesday. A week later a semi-truck is going to show up and literally drive into the cellar room at Magnolia and, like some kind of transponder, morph into a mobile bottling line.

So you see, putting a bottling package together is not unlike building a house, on a very small scale. There’s a drawing for everything. Then there are samples, proofs and sign-offs to deal with, and in my case the “new customer vetting” process. Did I want to fill out a credit application or was I paying up front?

“Credit, please.”

“Well then we’ll need at least three credit references from people in the industry.”

“Well, I’ve never really bought anything at this scale before from anyone in the industry.”

“No worries, we’ll send you an invoice in advance and once that’s paid we can ship your purchase.”

Ka-ching [cue up Pink Floyd’s Money], Ka-ching, Money… it’s a gas…

Labels

I’ll admit, I have a bit of an advantage—at least monetarily if not creatively—with the design/printing/production side of things. I’ve been doing graphic design and high-level production printing for paper-based projects from direct mail campaigns, to books, to consumer magazines, for nigh on 50 years. I even wrote a bi-monthly column on the subject for a while, for the magazine industry journal Folio. You can see some of that work on my creative production website www.storyartsmedia.com.

So, it’s not like I needed to hire someone for those services. Furthermore, one of the best things that comes out of that much experience is knowing how to source and buy printing, and utilize special techniques to produce amazing results without selling the family vineyard. I used all of that and more producing the labels for my first commercial wines because, trust me, wine labels can get very expensive very quickly! Ever walk through a wine shop or wine aisle in the grocery store and finger the beautiful gold-foil, embossed labels printed on thick, creamy paper with layered graphics? Ever wondered what that cost per label? Spoiler alert! You weren’t thinking high enough.

It’s easy to spend a buck or more per bottle for labels (remember you need two, front and back). I got to seventy cents without even trying. Now multiply that by how many bottles you’re producing—even a micro winery producing a negligible 1,000 cases is producing 12,000 bottles. You do the math.

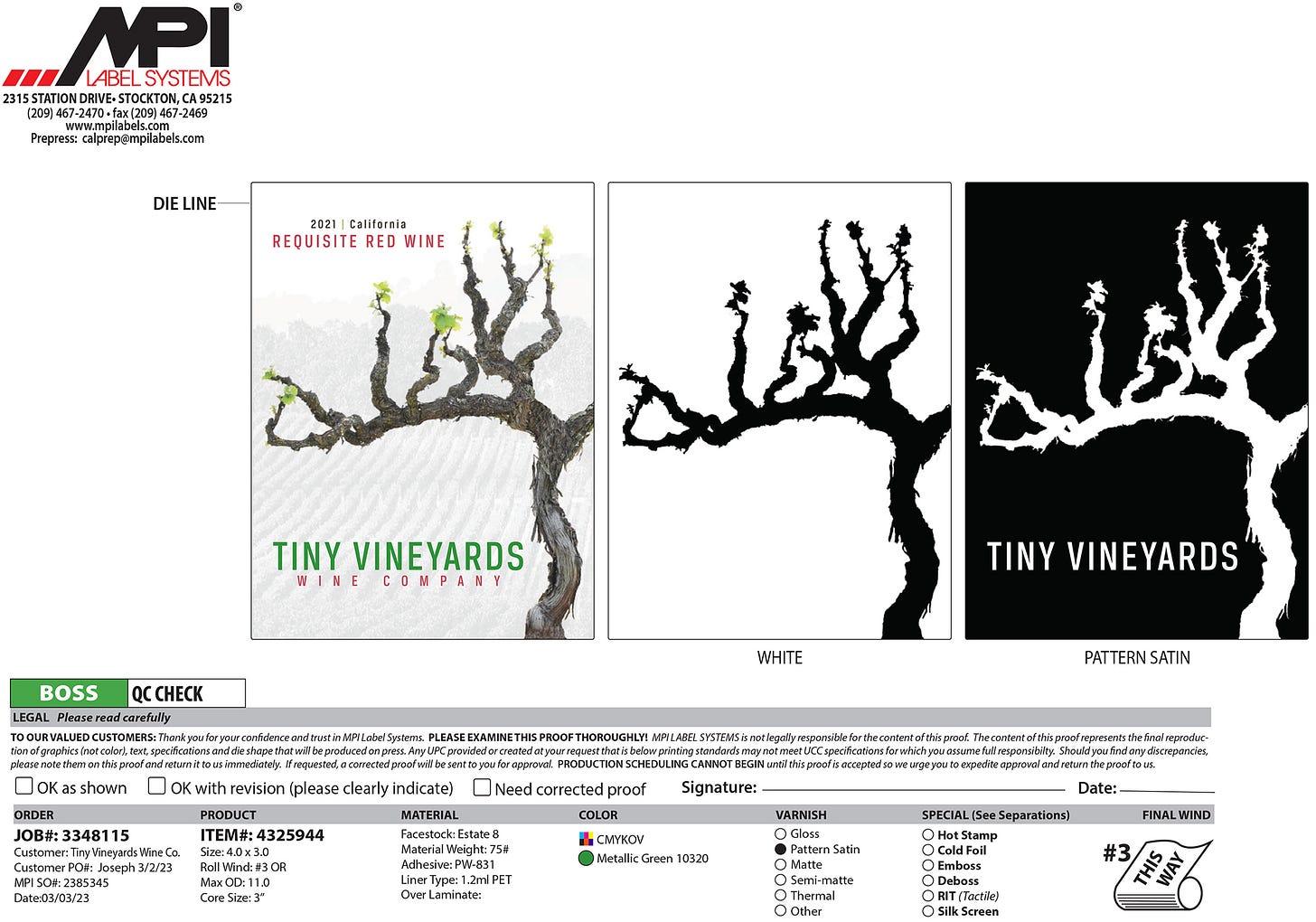

So I had to find a printer willing and able to create art at craft prices with journeyman tricks. And you know what? The very first (and subsequently only) printer I talked to at the Unified that day was the one that Ken used for his labels (which are stunning, by the way). And with his introduction I was literally enveloped by one very sassy Leticia White who let it be known right from the onset that my search was over and MPI Label Systems was going to be my printer.

Yeah, yeah, I thought. I’ve been overwhelmed by printer reps before, and nine times out of ten it all just turns out to be bluster. But there was something in Leticia’s demeanor that caught my attention. Just enough carrot on the stick without over promising. I decided to humor her and laid out some specs.

“Okay, so I want to do some four-color digital printing on a nice, slightly textured white stock, with embossed TINY VINEYARDS type hot-stamped in a colored foil.”

“Uh, huh. So what if we use this gorgeous Estate 8 stock paper [she cooed as she placed a printed label sample in my hand, and stroked it with my other hand]. This is what a lot of the higher-end wineries are using because it’s bonded to an opaque film on the back so the dark color of your wine and bottle doesn’t bleed through and snuff out your brightness. Then let’s isolate that vine and lay down some white ink underneath, which we’ll then overprint in process, further brightening the vine and creating some perceived dimension. Who needs embossing?! We’ll use metallic green ink instead of the hot-stamped green foil—just trying to save you some money, baby—and then we’ll apply a pattern satin matte varnish over everything except we’ll mask out the vine and the TINY VINEYARDS type, which will make them pop even more.”

“Wow, how much is that going to cost, per label?”

“I don’t know. Rough guess, maybe fifty cents.”

Sigh, I was in love.

And this coming Wednesday, Leticia’s prediction of who was going to print my labels is going to come true as I venture to Stockton for an early morning press check at MPI Label Systems.

Corks & Capsules

During my home winemaking days, the DIY ethos was well instilled and saving a buck was the mantra. For instance, when it came to saving money at bottling time, we all tried to figure out a way to score some corks without actually having to buy them, or having to buy them at retail, or having to buy them by yourself—better to share the cost of a full bag of corks with some winemaking buddies.

If you lived in an area that had a lot of commercial winemaking, all of this was pretty easy to do. Wineries were often quite happy to deeply discount or even give away a thousand-count bag of corks that had "aged out" (read that, dried out or were no longer sanitized). And you could actually save $400 to $500 if you were bottling your full legal allotment of 200 gallons of homemade wine per household—that’s 1,000 corks!

Of course, the obvious problems arose. You might end up with too many corks to go through in a season so you saved them until the next year and hoped they didn't dry out even further; you were often dealing with a previously sterile sealed bag that had already been opened and exposed to who knows what or where; you were trying to use corks that didn’t always quite fit the different size bottles that you had also scavenged; the corks were pre-printed with a winery’s name and logo and/or vintage date, which all had absolutely nothing to do with your wine; and the big risk—TCA (2,4,6-trichloroanisole) taint—from an infected batch of corks.

But the reality was—or was for most of us, anyway—that you could usually get away with it. Until I didn't.

I had made two fantastic homemade wines in 2020, a Pinot Noir and a Grenache/Syrah/Mourvèdre blend, that I was so proud of, but am now almost too scared to pour. It seems about one in ten bottles has "something" wrong. Something I can't quite put my finger on, but definitely a moldy-like degradation of taste and aroma. And after everything I’ve learned this year in my Wine Stability and Sensory Analysis course, it could really only be one thing, given that both of those lots of wine were bottled at the same time as several others, all under sanitized conditions and into clean bottles. But the Pinot and the GSM shared a bag of corks that the others didn’t. Corks which I had gotten for free from a friend of a friend, and which were undoubtedly randomly tainted with 2,4,6-trichloroanisole (TCA).

According to an article in Wine Enthusiast magazine, TCA is formed in the bark of the Cork Oak Tree when fungi, mold or certain bacteria come into contact with a group of fungicides and insecticides, collectively referred to as halophenols. These were widely used during the 1950–1980s and remain in the soil. Fungi have a defense mechanism that chemically alters these compounds, rendering them harmless to the organism but creating TCA in the process.

Suppliers make corks for wine bottle closures out of Cork Oak Tree bark and, unfortunately, they don’t always know if parts of that bark were contaminated with fungicides or insecticides. If they were, their resulting corks would damage any wine they touch.

Cork taint might have been acceptable, or at least not surprising, in those laissez-faire days of playing garagiste, but now that I’m so close to bottling my first commercial wine, with thousands of dollars and a brand-new unsullied reputation on the line, the very thought of having a 10% chance of loading a TCA bullet in an enological game of Russian roulette gives me the shakes.

And so, I did a deep dive into closures this year, even considering other non-cork alternatives like screwcaps. But alas, winemaking does have a certain risk/reward element to it, and the reward can often be found in how your wine is packaged, i.e., perceived by the buying public. Sure, I know that beyond the infinitesimal amount of micro-oxidation a natural cork provides, screwcaps are just as effective as cork, offer a dual solution for closure and capsule, are quite a bit cheaper, and have no risk of TCA contamination. So, why argue with the obvious, right? Because… they’re screwcaps damnit. And try as I might, despite the alleged growing public acceptance, maybe even preference for screw caps, I can’t think of them as anything other than closures for cheap wine.

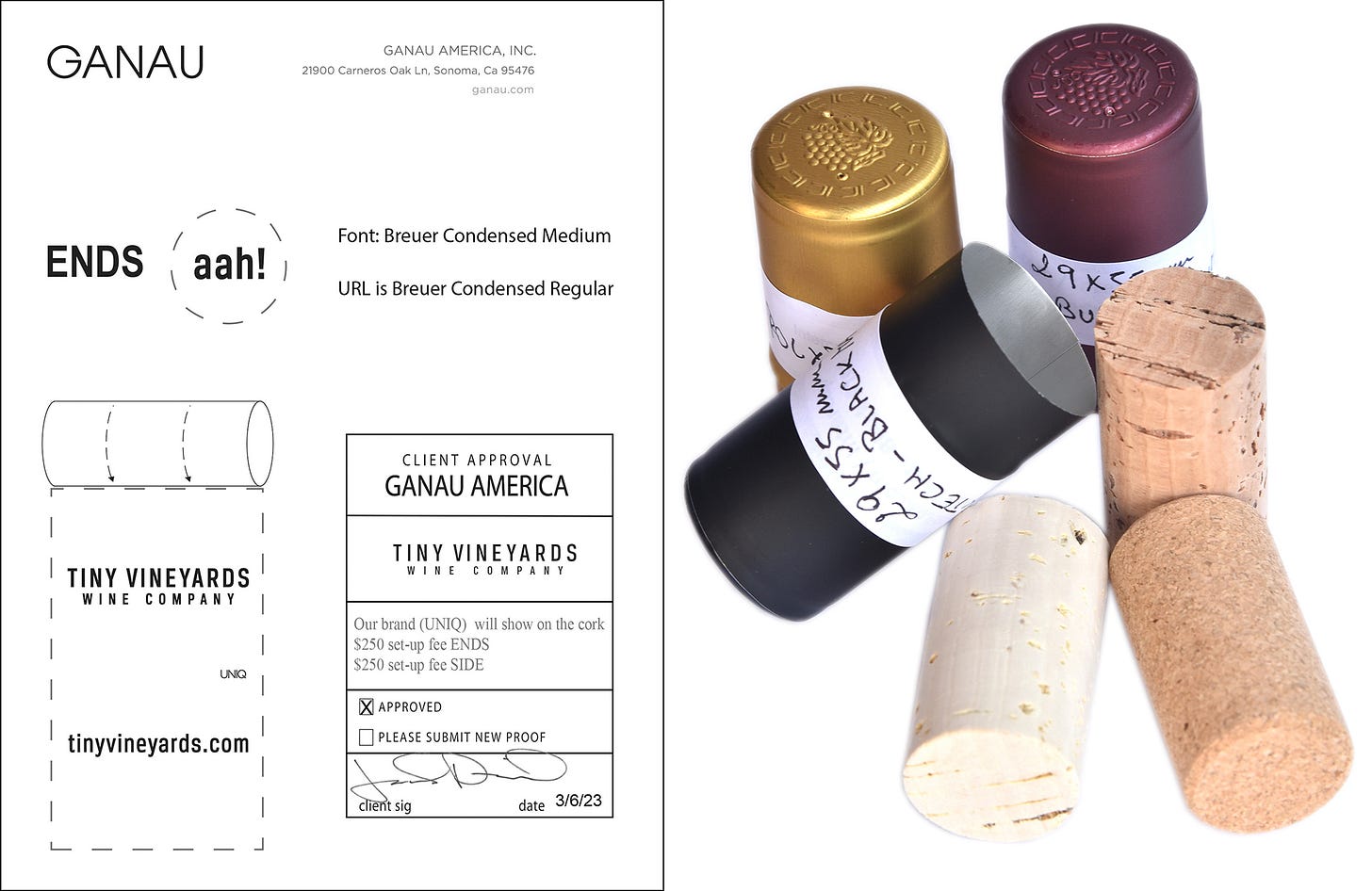

So, I sidled up to a wine bottle closure company called Ganau at the Unified—another one of Ken’s great contacts—and was given a lesson in cork. The first thing I learned was that quality grade corks that were consistently tested for TCA cost a lot of money. The second thing I learned was that there were great alternatives, especially with what is now being called a technical cork.

Ganau’s technical cork line includes a product called UNIQ, which is described on their website as, “Validated by several independent laboratories and considered the undisputed leader of technical corks, the UNIQ line represents the cork of choice for 21st century winemakers. Constructed from natural cork micro-granules selected for uniform sizing of 1mm or smaller, a neutral bonding agent, and high-quality microspheres, UNIQ offers superior organoleptic performance, rapid recovery rate, mechanical homogeneity and smooth extraction. It is the most advanced technical cork option available to winemakers looking for superior technology, cleanliness and dependability.”

Being the 21st Century winemaker that I am, this all spoke volumes to me, as did a price tag nearly 50% cheaper than quality natural corks. When, after some additional due diligence, I discovered that an increasing number of premium wines were being bottled using this type of closure, I was sold.

The final part of wine bottle packaging is what’s called the capsule—that colorful wrapping at the top of the bottle that you inevitably fumble with every time you attempt to open one. They were originally made to protect the cork, using soft lead to conform perfectly with the bottle’s rims and ridges at the top, but that was phased out partly due to fears that trace amounts of lead residue could be transferred to the wine during pouring, but also because it was winding up in landfills.

Capsules are now made out of heat-shrink plastic to be heat applied, or PVC plastic, aluminum, or tin to be spun on like the old lead version. Alternatively, with the ability to print brands, logos, even messages directly on your corks there has been a recent trend to go commando, if you will, forgoing any capsule at all. This is especially true with wines that will be consumed within a year or two as there is no practical reason to protect the cork for that short of time.

But the designer in me was all about the capsule, wanting to coordinate colors with the metallic inks used on the label, as well as customize it with our TINY VINEYARDS brand. When I discovered that I was way too late and far too poor to do that for this vintage (customized capsules are all manufactured in Europe and take two to three months to be made and shipped back), I shifted gears and decided to brand my corks instead. Ganau was also able to provide me with generic capsules in three different colors and a graphic grape cluster embossed on the top, although I had to buy 5,000 of each color. Being tiny is tough in the wine industry!

Future storage

The last thing I had to arrange was for a place all my wine could go once it was bottled, packed into cases, put on pallets, and wrapped in plastic. This had to be somewhere that offered safe, climate-controlled, legal storage in compliance with all TTB bonded wine and excise tax-paid wine storage requirements.

Jack, the boss man at Magnolia, wanted all bottled wine out of the facility within a few days, but where would I take it? And how would I get it there? I’ll have four pallets, an estimated 285 cases in total, that will need to be stored for at least another six months, but I also need easy access to it to extract sample bottles, marketing inventory and early sales. I hadn’t really sussed this issue out very well, and didn’t really know where to start.

As it turns out the answer was right under my nose, or more accurately, just across the parking lot. Magnolia Wine Services is located at one end of one of two twin commercial warehouses right next door to each other. A much bigger custom crush facility, Sonoma Valley Custom Wine, is located at the other end of the other warehouse—just a few hundred feet away. It also turns out that SVCW offers wine storage services, something we can’t do at Magnolia because we don’t have the room.

So it was just as easy as a simple exploratory email and a friendly tour, and I had a new home arranged for my upcoming wine. And Jack said he would just drive my pallets of wine over using a forklift.

Sometimes it’s great being tiny in the wine industry!

Prepping the wine itself!

With bottling just around the corner, it is time for final wine prepping. We’re going to deal with the Requisite Red Blend and the Eclipse Malbec on Tuesday because red wines don’t generally require as much attention. But we have a lot to do with my Chardonnay and some of that happened just this past week.

To set the stage: I barrel fermented just shy of a ton of Chardonnay last fall and aged it sur lies in two once-used French oak barrels for six months. I inoculated one barrel with Oenococcus oeni bacteria to stimulate secondary malolactic fermentation (MLF), and I inhibited MLF with sulfur dioxide in the other barrel. The goal was to create a traditional oaked, buttery Chardonnay with a creamy mouthfeel in one barrel (the one with MLF), and a crisp, brightly acidic, fruit-forward, modern-style Chardonnay in the other (with no MLF). Then my plan was to blend the two barrels together for a special Chardonnay with notes of both styles. And guess what? It worked. And it’s delicious!

We did this blending on Tuesday, just five days ago, using a special extractor called a Bulldog, which transports wine from the barrel to the blending tank in a very gentle fashion by pumping nitrogen into the top of the barrel forcing the wine up through the Bulldog and out through a hose to the tank. There’s a glass lens near the top curve in the Bulldog where you can see any lies (settlement) that is picked up and readjust the Bulldog’s position for a very clean uptake.

Once we had both barrels transferred to the tank and blended, we then took a sample for analysis, which we got back Tuesday morning. All the chemistry looked great and it gave us the data we needed to properly dose the wine with a final addition of sulfur dioxide in order to protect it against oxidation and any possible microbial exposure during filtering and bottling.

The blending tank we’re using has a special pitted jacket that we filled with a solution of glycol and water that draws heat from the tank, much like your car radiator works, enabling us to drop the temperature of the wine inside down to just above freezing. We’ll keep it like that for another week or so to conduct a cold stabilization and precipitate any excess potassium acid tartrate (KHT) out of solution so some confused consumer doesn’t end up with harmless tartrate crystals in the bottom of his or her bottle and misidentifies them as broken glass. No kidding, it can be an issue with white wine.

So, stay tuned, next week promises to get just as crazy—maybe even more so!