Celestial Celebration!

Why you should absolutely reserve a few bottles of my Eclipse Malbec.

This is a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity for most people to see a total eclipse, and it is one of the grandest sights in all of nature. It's something you'll always remember, and you'll pass stories of it onto your grandchildren. —Fred Espenak

The return of the Sun after a total eclipse . . . spoke to our ancestors of the possibility of surviving death. Up there in the skies was also a metaphor of immortality. —Carl Sagan

Darkness at the break of noon/Shadows even the silver spoon/The handmade blade, the child's balloon/Eclipses both the sun and moon/To understand you know too soon/ There is no sense in trying. —Bob Dylan

Last one in the United States for 20 years!

On April 8, 2024 a spectacular total solar eclipse will race across North America. Its umbra—the moon’s shadow where it is darkest from having totally eclipsed the sun—first touches land at Mazatlan. It then travels northeast through Mexico and enters the United States at Texas, cutting a diagonal all the way across the country to Maine, then exiting through the maritime provinces of Canada. The duration of totality will be up to 4 minutes and 45 seconds, almost double that of the 2017 eclipse that also crossed the country, and it will be the last total solar eclipse that can be seen from the contiguous United States until 2044. So yep, it’s a biggie!

According to greatamericaneclipse.com, anticipation for the April 8, 2024 Great American Eclipse is already sky high! “Not only are there 32 million people already living within the USA section of the path of totality, but metropolitan areas such as St Louis, Cincinnati, Detroit, Toronto, and Quebec are very close to the path, and the major cities of Boston, New York, Philadelphia, Baltimore, and Washington, D.C. are all within 200 miles of the path of totality. Be prepared for the single-biggest mass travel event in the USA.”

If you’ve ever actually witnessed a total solar eclipse you’ll probably agree with me that any description of the event—one that actually does it justice—is pretty much beyond words. But, read this century old recollection by Mabel Loomis Todd to come close.

Properly experiencing a total solar eclipse requires three things:

1) A pair of safe viewing glasses.

2) Viewing proximity within the 100% totality zone (99% doesn’t cut it, you need to be within 100% totality to see the sun’s corona).

3) A willingness to give yourself over to the sky-shattering beauty and extremely powerful emotion of the event, and to fully celebrate this stupendous act of nature.

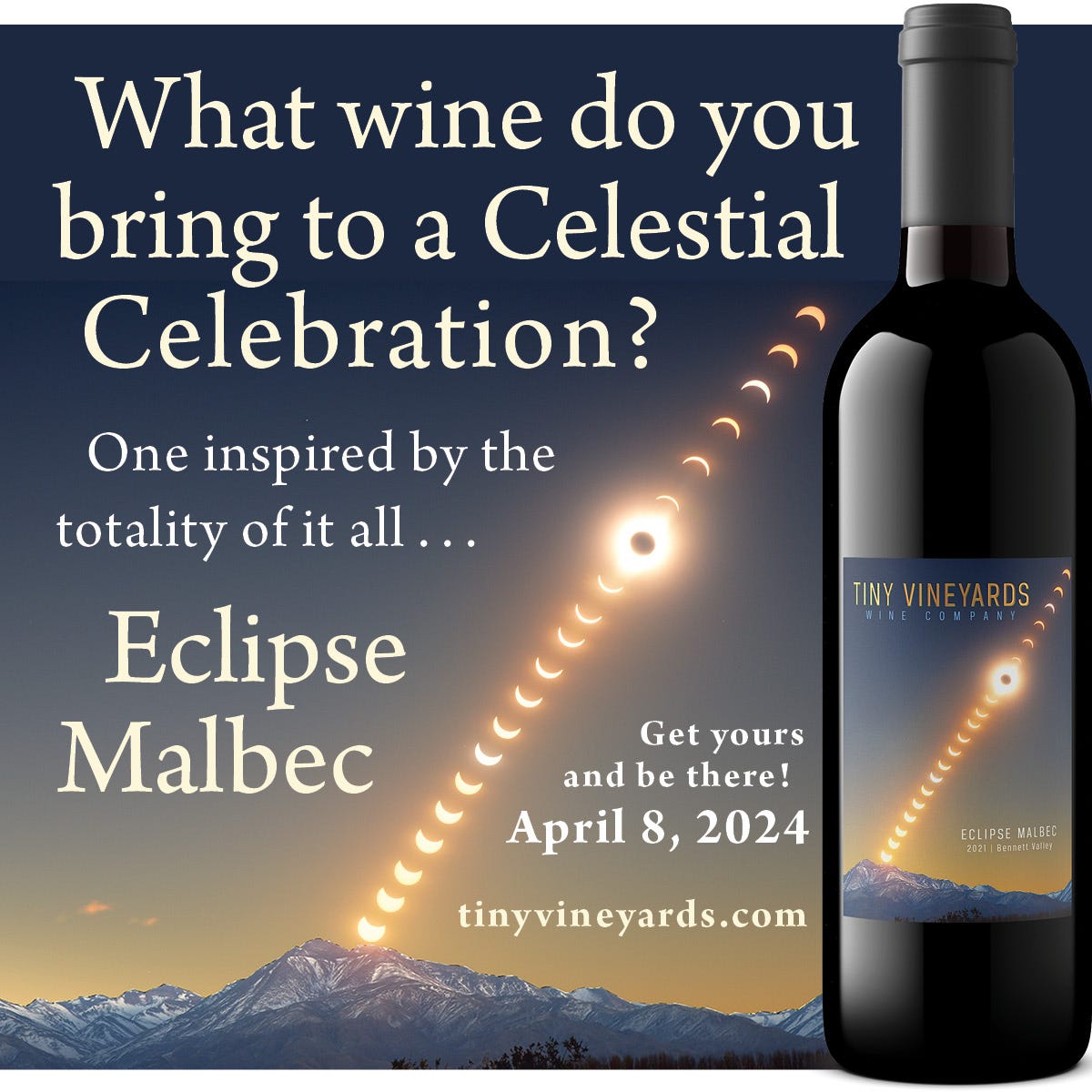

That’s where my wine comes in. This 2021 Eclipse Malbec was inspired by a total solar eclipse composite I photographed (hence, my label) over the Andes Mountain range near Mendoza, Argentina, in 2019. It was handcrafted specifically for celebrating the upcoming 2024 Great American Eclipse as it traverses North America.

Here is the story of its genesis.

A collision of wine and the heavens

Montana - February 26, 1979

The first total solar eclipse I ever saw was on February 26, 1979 while hunkered down in a bleak, frozen field in northern Montana. I was a 24-year-old photographer working for a tiny newspaper in Boulder, Colorado. A friend who was really into astronomy invited me to join him and a car full of his similarly affected pals on a “quick” 680-mile road trip to the Fort Peck Indian Reservation a few miles south of the Saskatchewan border. It took us 12 hours to get there.

But that was of little consequence. The last time a total solar eclipse had been this near to my home state of Colorado was during the year and month I was born. And it wouldn’t happen again in the United States for 38 more years. These are truly “better grab ‘em while you can” events.

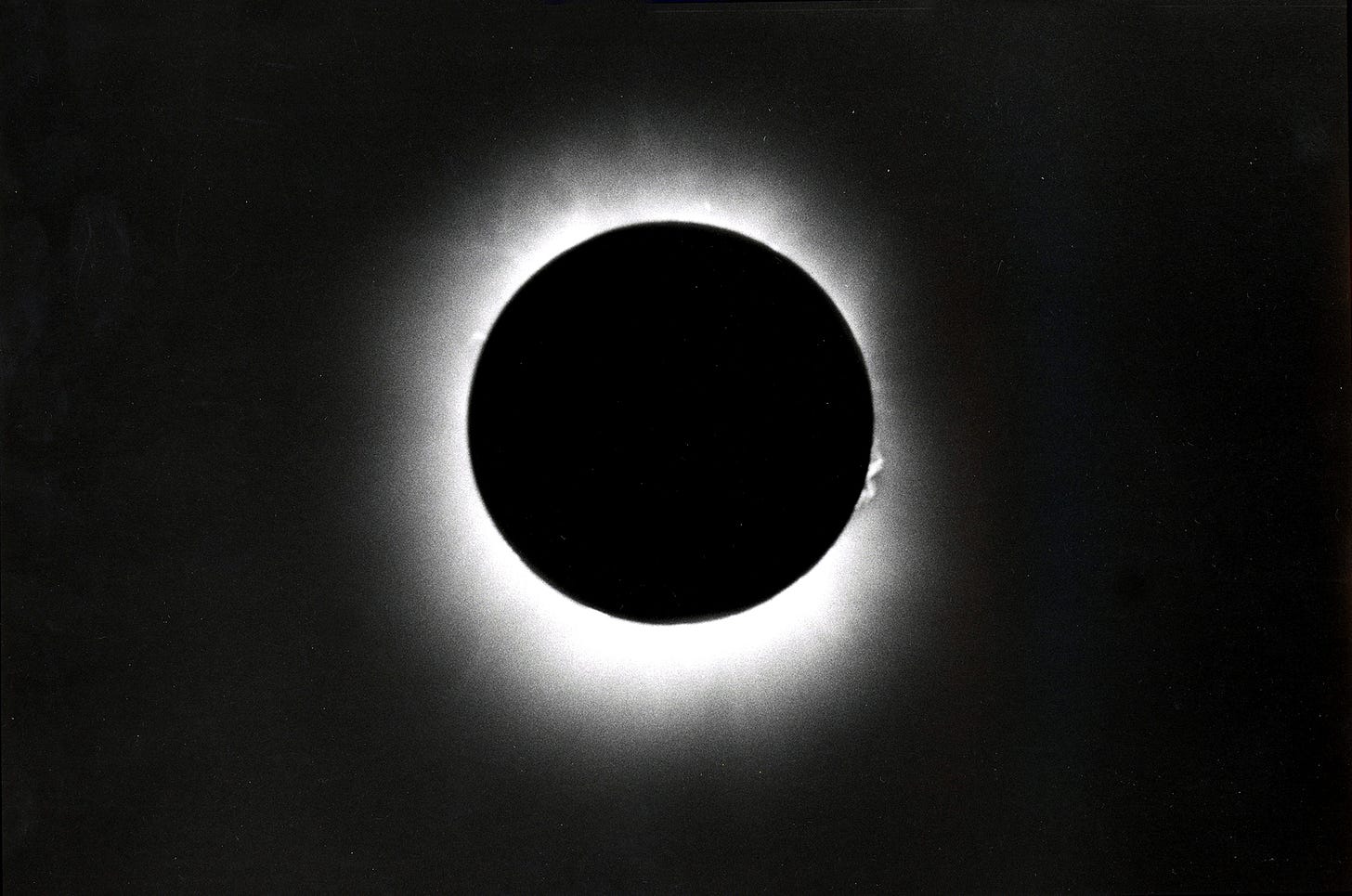

Despite the cold, winter conditions—and the very real chance that we were going to be clouded out—the skies cleared as if on cue, and the moon punched a fire-rimmed ink-black hole in the heavens. Somehow—because I was ostensibly up there on assignment for the newspaper—I managed to get a photograph of the eclipse during totality.

But mostly I just stared in disbelief.

Kenya, East Africa - February 16, 1980

A year later, almost to the day, I found myself camped along the banks of the Tsavo River in Kenya, East Africa. My father, a professor of biology, had been on a Fulbright to the University of Nairobi, and my mother was working as a library scientist for Richard Leakey (yeah, the one of anthropological fame) at the National Museum. I was over there visiting them, and a girlfriend who was working for the Peace Corps in Uganda.

A total solar eclipse just happened to be occurring in East Africa at the same time as my visit and the path of totality ran directly through Tsavo National Park, a remote, seldom visited wildlife refuge in southern Kenya. Leakey, and his staff at the National Museum had set up a camp there to study the effect of the eclipse on animal behavior, and through my mom’s association with them we were invited to come along. After seeing my first eclipse in Montana I was very excited about the possibility of witnessing another one, especially in the wilds of Africa.

It was all as fanciful and exotic as it sounds, and my dad’s description of the event—taken from his biography—tells it as only a biologist could. “We had to arrange for our own equipment and transportation, which was not very difficult, and so accepted their invitation. Joe was visiting us at the time so he and a girlfriend joined us for the weekend. We drove in a Land Rover to the Tsavo River, where we set up two tents and a cooking area on one bank about 100 feet from the Museum’s camp. When the full eclipse started, nocturnal spiders began to weave new webs, storks that were fishing along the river assembled and flew off, and a large troop of baboons became highly agitated, fearful at finding themselves far from their nesting trees with darkness coming on. After their frightened shrieking had subsided the place became strangely silent with confused animals as the light faded and then, moments later, erupting into a cacophony of sound when the daylight returned after that short “night.” We stayed in our camp one more night and the following morning we awoke to find lion pugmarks in the soft ground between our two tents!”

Baja, Mexico - July 11, 1991

Eleven years later I was on the eclipse chase again, this time on a rocky beach below Rancho Buena Vista, a tiny remote fishing camp hugging the Sea of Cortez about a sixty miles north of Cabo San Lucas, Mexico. I was publishing an environmental magazine at the time, (Buzzworm: The Environmental Journal and here) and a friend who owned an eco-tourism company in La Paz had called to say they were staging a serious eclipse camp for amateur and professional astronomers and would I like to come down to do a story. He had no idea what buttons he had just pushed!

I convinced a few pals to join me, including my friend who put together our original eclipse trip to Montana, and we all headed to the tip of Baja. That same friend was so profoundly impacted by what would be his second total solar eclipse that it actually influenced the trajectory of his life. Reminiscing with him just a couple of weeks ago, he sent me this email. “A winter eclipse [Montana] started it and you thought why not do more and went to Africa. Then we did the barn-burner longest of our lives in Baja for Buzzworm, and for me it all changed there. Not only one of the best (FUN) trips of my many in life (and meeting Perry [Hacking] & the Rubins there) but realizing I can never stop — now 14 of them, 40 minutes, 9 seconds of shadow time later.”

Eclipse chasers call their accumulated total of solar eclipses witnessed “Shadows Done” and their accumulated time in the shadow of 100% totality “Shadow Time.” Check out my friend’s website, he has an impressive eclipse log with terrific photographs and remarkable radio reports from places unknown. He would connect with several professional and serious amateur astronomers at the Baja eclipse and go on to join them on shadow expeditions around the world.

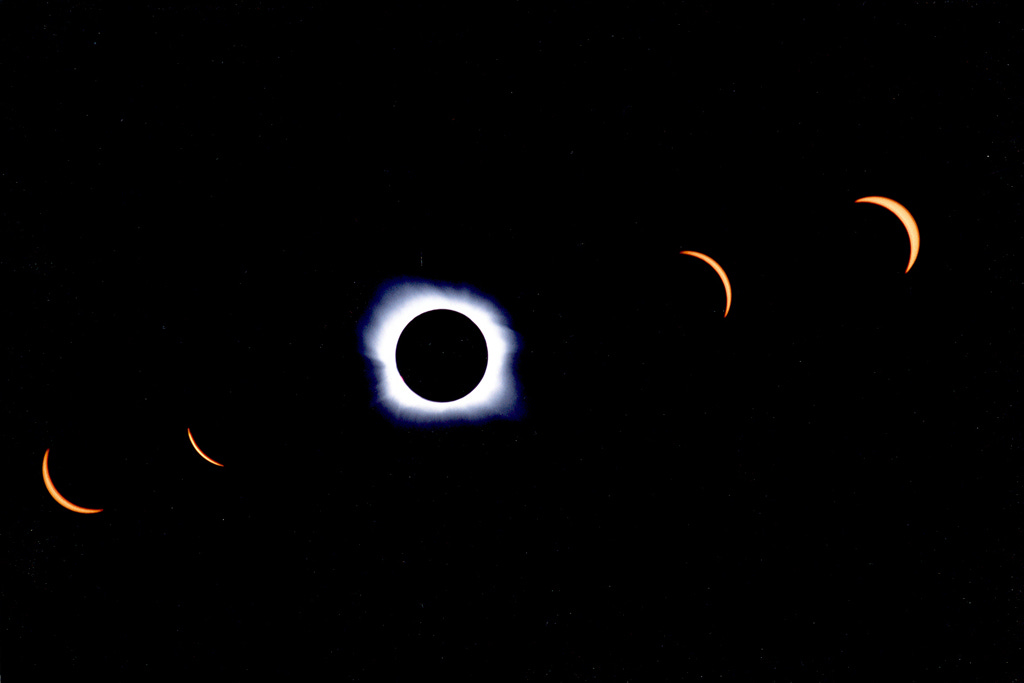

As for me, I approached Baja with three goals in mind, 1) to write a story about chasing the sun, 2) to shoot a time-lapse multiple-exposure photograph that somehow showed the sun’s crescent as it disappeared into totality and as it emerged again to the utter relief of everyone watching. Somehow, I pulled it off, as described in the caption under the photo above, and, 3) to bask in the celestial darkness once again—for the third time—adding an astonishing 6 minutes and 53 seconds to my shadow time and reconfirming the reality and the fragility of our solar system. And perhaps the existence of something even bigger than all of that.

Oregon, August 21, 2017

It would be 26 more years before I was to witness another total solar eclipse. Life got in the way—children, career, finances. There had, of course, been many of them during that time but always somewhere tough to get to—Thailand, Hungary, Zimbabwe, South Africa, Egypt, Siberia, China, Australia, Indonesia.

But I was on walkabout in 2017, trying to comprehend a dying marriage and finding solace in the land. The cultivation of land. Getting my hands dirty and doing the honest work of the common man. The hundreds of thousands of acres of wine grapes planted in northern California had caught my attention. Not because I knew anything about them. But because I didn’t.

Then I heard about “The Great American Eclipse,” a total eclipse of the sun on August 21st that would transect America from the Pacific coast of Oregon, across 14 states, to the Atlantic coast of South Carolina. Are you kidding me?! A total solar blackout right in my backyard, right in a huge number of backyards. A “great” eclipse indeed!

There was no way I was missing this, and I set about planning how I would watch it. When you’re an eclipse chaser the first thing you do is look for a location within the path of totality that offers the best chance for clear weather. Any clouds in the forecast and it can mean disaster. My friend with whom I had traveled to see the Montana and the Baja eclipses was already sussing out a remote location in Wyoming that he was convinced would be nothing but blue skies. He was planning a genuine festival for a large group of eclipse virgins and encouraged me to come along. But I had other plans.

Being in the beginning stages of my “wine awakening,” I wanted to watch the eclipse from a vineyard. I wanted to truly celebrate the event with good food, great wine, music and frivolity. I wanted (needed) to experience that ancient sense of surviving death, of new life, of the immortality that our ancestors felt whenever the sun returned from totality. And I found just the place in the Willamette Valley of Oregon.

Eola Hills Winery was planning a festival of their own, with unhindered eclipse viewing possibilities, great food served every which way including a special sit-down dinner in the vineyard, music all day and into the night, and thousands of bottles of Total Eclipse—a 2016 Pinot Noir bottled with a special label just for the occasion. The wine was truly good, which made everything else perfect.

There are certain stages of a total solar eclipse that you look for (and can see in the video above). Without safety glasses nothing really seems all that different about the day until you’re just minutes away from totality—the sun is that bright. That’s why it’s kind of a non-event if you’re not in the path of totality.

With safety glasses, however, you can literally watch the moon from “first-contact” taking ever enlarging bites out of the sun over a hour and a half or so, down to where it’s only a tiny crescent. At that point you might see undulating lines of light on the ground called “shadow bands,” or even miniature eclipses projected like a pinhole camera image where the remaining sunlight is focused through tiny holes between leaves and branches.

The next phase is called “second-contact” where the moon is about to truly eclipse the sun. Towards the end of this phase you may observe the phenomenon of “Baily’s Beads.” These are distinct balls of light visible at the edge of the moon’s circumference that are caused by the sun shining through craters on the surface of the moon. These beads will flicker off one by one until one solitary point of light remains. This is known as the “diamond ring” effect. It lasts just seconds but produces one stunning single burst of light.

In Oregon, I sent a drone up about five minutes before second-contact as I wanted to film the umbra—the moon’s shadow—racing towards us. As it envelopes everything the sky darkens perceptively, the temperature drops, birds stop singing and other animals and wildlife exhibit nighttime behavior. You may experience a feeling of dread or nervous excitement. Listen to the people around you!

Totality takes place when the moon covers the entire surface of the sun. You can, and should, take off your protective glasses for this phase as only the Sun’s corona is visible. The sky is now a very dark deep blue, but not as dark as night. The moon eclipsing the sun is as black as ink. I always think it looks like someone punched a hole in the sky with a paper punch, and that hole is on fire! If the Sun’s solar activity is strong, the corona will blast out from all sides of Moon. If it is weak, it will follow the direction of the Sun’s magnetic path. Take a moment to spin around in place looking at the horizon— a 360° sunset!

As totality ends you can observe first- and second-contact phenomenon again, only in reverse, diamond ring, Bailey’s Beads, shadow bands and those little projected eclipses. The sky brightens, the temperature rises, and the birds begin to sing again. Time to put your protective glasses back on—the sun has returned!

The Oregon eclipse was reaffirming, more so than I had even hoped. I was back on the eclipse circuit after more than two-and-a-half decades, with ten future “gettable” total eclipses still to come in my foreseeable lifespan. I also had the special opportunity in Oregon to share the whole experience with my partner Deb, her unfettered excitement and awe at witnessing her first eclipse confirmed the powerful emotion and sheer spectacle of it all.

Oh yeah, my friend who set up his eclipse camp in Wyoming? Huge success!

Argentina, July 2, 2019

If Oregon was my intersection between a total solar eclipse and wine, Argentina was a full-blown head-on collision. The eclipse of 2019 would make landfall in Chile, climb eastward over the Andes Mountains and pass directly over the tiny town of Bella Vista, in San Juan Province, Argentina just 210 miles north of Mendoza—the Malbec capital of the world. Getting the connection yet?

Deb and I, and our friend Donna and her brother David, would rent a tiny camping cabin in Bella Vista that I had arranged for so far in advance that I think the proprietor was scratching his head wondering who we were when we arrived. But it was a smart move as hundreds, okay likely thousands, of people flowed in from Mendoza the day before the eclipse and every patch of ground for even just a small tent was taken.

The Argentine government leaned into the event big time, producing a rock concert-quality happening on several acres of land just south of Buena Vista. They erected a tent city of food, wine and eclipse-souvenir vendors, a huge jumbotron that projected a live image of the entire length of the eclipse in splendid definition, ample porta-potties, and ordered parking for hundreds of cars and buses—all the while blasting a very loud hi-fidelity selection of Latin pop that kept the crowd energized.

David went with us to check it out but was quickly dismayed by the carnival atmosphere and left to find a quieter viewing location. But I love the human involvement and reaction to an eclipse—the more the merrier—and we made our way to the western edge of all the madness to stake out a position and set up our cameras.

I rigged a video camera with a wide angle setting to capture scenes of the crowd, and a wide view of the eclipse in time-lapse (video above). But what I was really after was a series of still photographs I could use to create a composite image of the eclipse as it went through its partial stages on both sides of totality. This still required some quick filter changes and some ridiculous exposure equations to handle the totality section. But again, I got lucky and got it right, and was thrilled with the result (see ad below). What I had no way of knowing back then in 2019 was that this image would become not only the label, but the very foundation of a social media ad campaign for my Eclipse Malbec, a wine I would make during my inaugural professional vintage two years later.

After our blown minds came back to earth to unite with our physical bodies a day after the eclipse, Donna and David began making their way back home and Deb and I headed south to Mendoza for a deep dive into the belly of the Malbec beast. We visited the famous wineries in the area, bought roadside samples of homemade wine, and drank the elixir at every meal. We crossed into Chile and did the same thing, never satisfied that we’d had enough but fully cognizant that we were being treated to something rare and special.

So, what more can I say?

After this upcoming total solar eclipse on April 8, 2024, the next total solar eclipse that can be seen from the contiguous United States will be on Aug. 23, 2044. Missing this one is tantamount to missing the coolest thing you might see in the next 20 years. So, mark it down in your long-range calendar and start considering where you might want to be when the moon next eats the sun. We’re thinking Texas! But here’s a fabulous resource loaded with information on the best viewing locations across the country, and so much more.

Then, if you haven’t already done so, head to tinyvineyards.com and reserve enough of my Eclipse Malbec to properly celebrate this grandest sight in all of nature. Or, if you won’t be able to attend the eclipse (oh, but you should!), give one of the coolest gifts ever to someone you know who will be there this coming April. Do this now before the prices go up, which they will as soon as we begin advertising.

I absolutely guarantee you will not regret it—the eclipse and the wine!