First Vintage

Divine providence or beginner's luck?

And Noah, a husbandman, began to till the ground and planted a vineyard, and drinking of the wine was made drunk, and lay naked in his tent. — Genesis 9:20-21

In the beginning

When I was about ten years old I remember my dad announcing that he was going to make wine in the garage. Now this wasn’t all that strange as my father was a fearless do-it-yourself guy, and as a research biologist his curiosity about things was expansive. He once tried to age a goat carcass in the garage, “to get the meat tender, like they do in Mexico” and was convinced it was proceeding as planned until my mother demanded he bury it outside due to the fetid smell of putrefying flesh seeping into the house.

Dad built a wooden canoe by himself, then he built an entire house by hand out of leftover flagstone he scavenged from a construction site at Adams State University in Alamosa, Colorado. This is where he first worked as an associate professor, and where I was born. And it was where he took me and my siblings, as toddlers, along with him collecting red-winged blackbird eggs as part of his doctoral thesis, and then surveying wildlife in Great Sand Dunes National Park & Preserve for the National Park Service. He discovered a new species of tiger beetle there on one of those trips and would occasionally capture a sidewinder rattlesnake to our collective shrieks of excitement.

He taught himself to play the cello, then subjected each of us to the torture of music lessons on our (his!) chosen instruments. He taught us to a shoot bow and arrow and ping tin cans with a .22 rifle. He fed us quail eggs for breakfast and rabbit for dinner so frequently we all thought they were just chicken; they were actually research animals from his lab that he felt bad about killing and hated to waste. He fancied himself a gourmet cook, which he wasn’t, but my mom gave him just enough rein to afford herself an occasional breather from raising six rambunctious kids.

As the scope of his research grew he traveled to increasingly exotic places and he never failed to bring back incredible gifts from his trips. I remember a carved walrus tusk from the Arctic, a leather and stone bola from Bolivia, and a real boomerang from Australia. By then our hometown was Boulder, Colorado, but his career took us on family moves to Alaska, then England, then Tennessee, then Africa.

His work was just as diverse and remarkable—groundbreaking research on delayed implantation with the discovery of blastokinin, an important protein that allows some mammals, like seals, bears, armadillos and kangaroos to get pregnant but delay embryo development and birth until conditions are favorable; a National Science Foundation Fellowship to Cambridge, England, where he got the opportunity to assist in the original “test tube baby” research; a Fulbright Grant to Kenya where, amongst other things, he studied the visual acuity of rhinoceros (I had the perilous job of hiding behind and steadying a life-size photo cutout of a rhino, while he recorded how close we had to get to wild rhinos to elicit a response!); and an ill-conceived and short-lived venture cloning champion thoroughbred race horses. Imagine replicating Secretariat—I think that’s exactly what my dad was imagining! Ours was a charmed childhood of a distinctively different nature.

Dad could be a pretty strict, but finish your chores and stay respectful, and anything you wanted to do or try out he’d usually support—even get personally involved. Later in life he became an accomplished whitewater canoeist, raised seeing-eye dogs for the blind, wrote children’s books and became a Master Gardener. Throughout it all, if he wanted to do something, he just did it. No problem if he knew absolutely nothing about what he was about to attempt. He’d figure it out as he went along. And most of the time he was gloriously successful.

But back to that wine he was going to make.

My father didn’t know wine from whiskey, mainly because he didn’t drink. And when you live over a mile high in Colorado the only grapes you’re likely to come in contact with are used to make Welch’s grape juice, or grape jelly. So when he arrived home one evening with the trunk of his car full of concord grapes that he’d picked from some old vines growing on university property, none of us was the wiser—especially my dad.

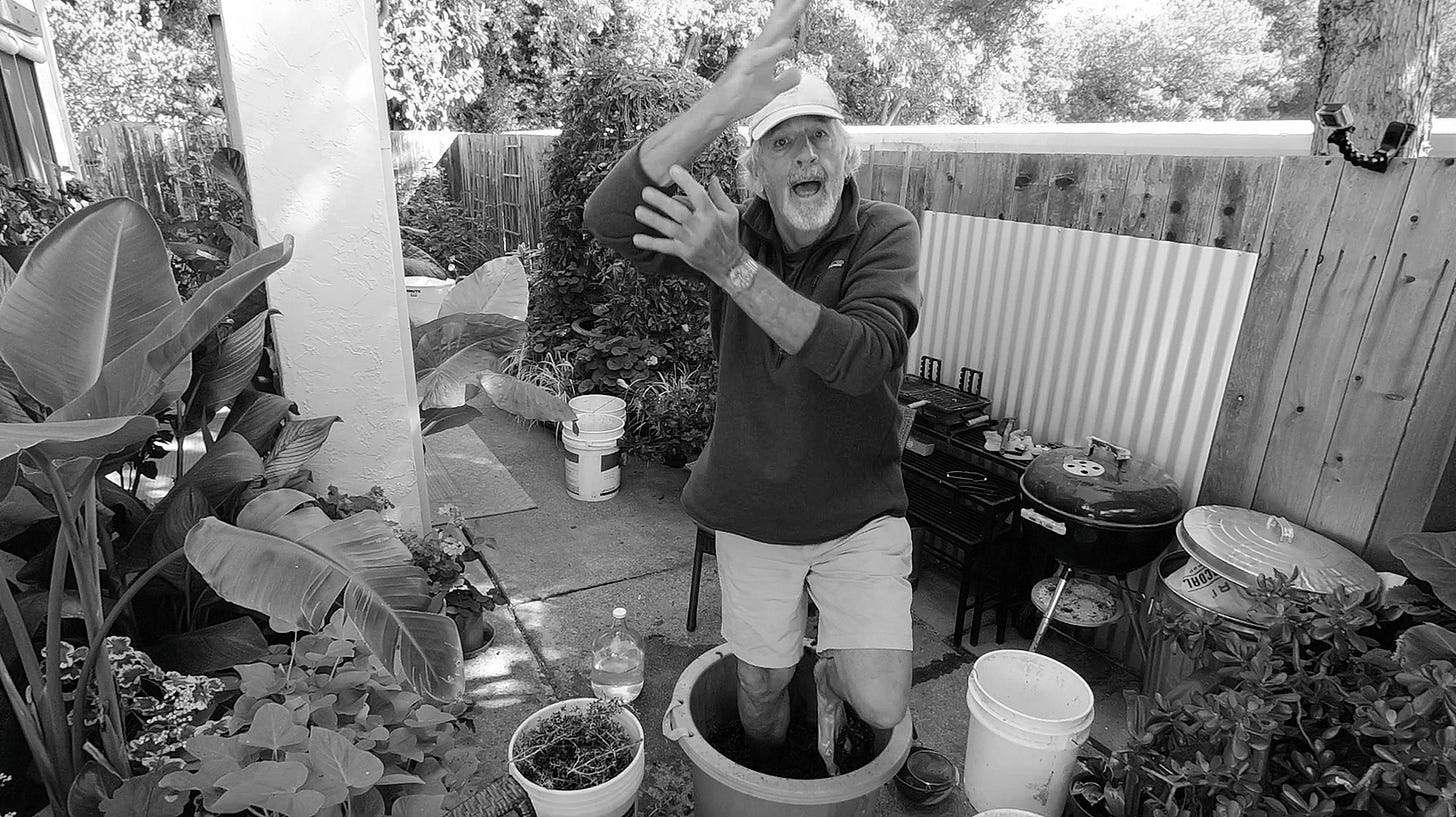

I can only recall bits and pieces of his winemaking, but one thing I do remember is our delight at being allowed to stomp on the grapes barefooted to crush them. I think he planned to ferment the wine in an old trash can and he lifted each of us in and out of it, over and over, for our turns mashing the grapes with our feet. Then he cautioned us not to disturb the container of grape juice, that it was going to take a long time for it to turn into wine.

We all soon lost interest, and it wasn’t until many months later that we found my mom and dad out in the garage laughing hysterically. Something had gone terribly wrong with the grape juice and it hadn’t turned into those expensive bottles of French wine that I’m sure my dad was convinced it would. In fact my mom kept saying something about a lifetime supply of vinegar, as they each took little sips and then cracked up laughing again.

Those of us brave enough got to taste it and it was horrible.

So that’s my providence, my legacy, for winemaking. And I’ll admit right now that when I was “re-introduced” to it in 2018—the year of making the Tiny Vineyards film—I knew little more than my father did way back then. But I echoed his enthusiasm and leapt right in with the same amount of ignorant bliss. Sure, in hindsight it’s pretty embarrassing. Total newbie stuff. But it’s also pretty funny, and downright amazing given the outcome.

You need the right grapes to make wine

The very first thing I learned was, sure enough, wine is rarely made from Vitis labrusca, my father’s infamous concord grapes. I also learned that the types of grapes that are used to make most varietals of wine all come from a single species, Vitis vinifera, which I find remarkable given the obvious differences between, say, Cabernet Sauvignon and Sauvignon Blanc! But it’s like domestic dogs; they are all of the species Canis familiaris, and yet so vastly different—Chihuahuas vs Great Danes?! What is most remarkable is that in both cases, grapes and dogs, all of those differences are the result of human intervention through, respectively, selective cultivation and selective breeding over thousands of years.

With all due respect to Darwin, humans have been messing with nature for a long time.

So yes, I needed grapes to have a go at making wine, and as I mentioned in my earlier post, Making the Movie - Part 2, I was able to scavenge up 100 pounds of a field blend of grapes from a second pick of John Diserens’s vineyards, and the same amount of Cabernet Sauvignon from Sam’s Vineyard through the largesse of Sal Troia. All I needed now was something to put them in, some way to crush them, and somewhere to call my winery.

I must extend my gratitude right now, loud and clear—and I can already hear her shushing me—but if it hadn’t been for the unlimited support and much-needed encouragement from my friend Debbie Tancik, and access to just about every room in her house, I would still be buying my daily red in six-bottle discount packs at Safeway. But Deb was unfazed (at least outwardly!), and that was enough to ignite those first few sparks of interest, which would grow into full-fledged passion.

So, in the spirit of “a picture is worth a thousand words,” here’s the story of making my first vintage, hopefully minus most of the boring details. They are, after all, just details, and as I recently reread the dense journal I kept that year I was struck by how totally clueless I actually was. If it hadn’t been for the generous advice of many of the home winemakers I had recently filmed, my story of first-time winemaking would have probably ended up similar to my dad’s.

For those readers who want to bone up on some basic winemaking-speak, check out this Glossary of Terms from morewinemaking.com. And if you desire a deeper dive on how to actually do this, refer to the excellent and very detailed Winemaking Basics from gencowinemakers.com.

First vintage

Professional winemakers will all tell you that making wine in the small containers that home winemakers use is much harder than doing so in traditional 60-gallon barrels. First there’s the issue of chemistry (particularly with the sulfur additions needed to keep the wine stable) in that you’re working with tenths or even hundredths of grams as a home winemaker, instead of ounces or pounds like the big boys. Hence any error in measurement has a potentially far greater effect. Then there’s temperature control. Small containers can become too warm or too cold relatively quickly, whereas big volumes of wine can take days to make significant temperature shifts.

Durability is another issue. A 5-gallon glass carboy is actually a pretty fragile thing, just heavy enough when full to be awkward to move and subject to catastrophic shattering if even lightly dinged the wrong way—everyone has a disaster story! However, a 60-gallon oak barrel full of wine weighs nearly 600 pounds and is practically bombproof.

And finally, there’s cleanliness. As my grandmother used to say, “cleanliness is next to godliness,” which should actually serve as a critical mantra for home winemakers, regardless of your beliefs. Commercial-size wineries have this dialed in pretty well with strict cleaning protocol and early intervention when things do go wrong. But nothing impacts overall success more for home winemakers than spoilage from bacteria, fungi and/or yeast. Every tool, container, hose and measuring device used in winemaking can be a vector for introducing those agents of spoilage, and just wiping them all down with cold water—often the standard practice with home winemakers—isn’t going to cut it. Perhaps a positive takeaway from our collective COVID-19 experience could be the sanitizing-wipe-downs-of-literally-everything obsession we all practiced, at least in the early stages of the pandemic.

Somehow, incredibly, I dodged all those bullets the first year I made wine. I bought a digital jewelry scale used for weighing gold to accurately measure tiny amounts of dry chemicals. I regulated temperature constantly with a small oil heater. I didn’t break anything full of wine—although there were a few close calls. And I kept a solution of three tablespoons of potassium metabisulfite dissolved into a gallon of water constantly ready for sanitizing wipe downs and cleanings.

However, it was my naive insistence on using small American oak barrels for aging, and being unaware of a simple construct of physics concerning the relationship between volume and surface area, that could have easily been my downfall. Simply put, as the size of a barrel decreases, the overall percentage of the wine inside that comes in direct contact with the wood increases, resulting in increased extraction of the oak qualities. New American oak has very sharp qualities (as compared to the French oak favored by most winemakers) with strong, tough tannins and the predominate aroma and flavor of vanilla.

My two first wines lasted less than two months each in these barrels before they were tasting more like cream soda than Cabernet, and had to be racked back into glass carboys for the rest of the year. I was convinced I had ruined them.

Gato de la Mancha

Around the time I was wrapping up those intense few weeks of making my very first vintage, and the wines were finally ensconced in a cupboard in Deb’s bathroom to hopefully complete malolactic fermentation, we adopted a rescue cat we named Bodhi—Sanskrit for “enlightenment.”

From the start Bodhi was a virtual predator, chasing mice of his imagination throughout the house at breakneck speed, only to suddenly leap up onto the dining room windowsill to literally quiver in feline fury at the real wild turkeys strutting across the front yard only a few yards away from his perch. The only enlightenment going on was with me realizing the impenetrable workings of a cat brain.

But over time Bodhi won our hearts and he was actually pretty good company as I sat chained to my chair editing Tiny Vineyards. He would jump up on the desk and threaten to flop across my keyboard, only to sashay somehow effortlessly between the keys, any misstep having the potential to destroy hours of work.

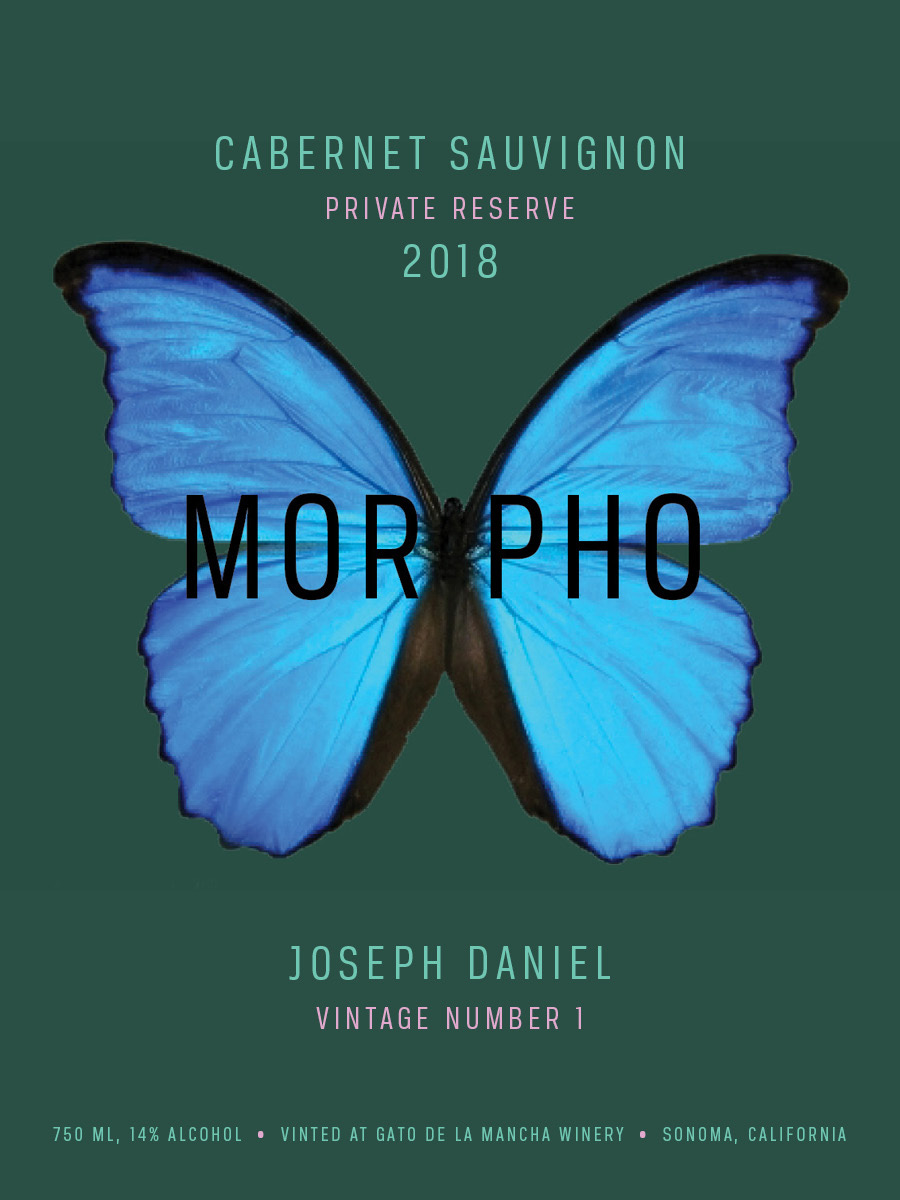

As I started to think about a label for my new wines I realized I needed to come up with, amongst other things, a name for my winery, which, again, was Deb’s house. She lived on a street named La Mancha, which never failed to make me think of The Man of La Mancha. Watching Bodhi one day as he pretend-stalked me from the hallway, and wondering what madness was messing with his imagination, I suddenly realized he was Don Quixote incarnate. So, with apologies to Miguel de Cervantes, and a nod to the Hispanic contribution to the area, my first venue for making wine was officially named Gato de la Mancha Winery.

Morpho

Okay, now for the label proper. My publishing/filmmaking company is called Story Arts Media and I use a blue morpho butterfly as the logo. My reason for that is described on the website as such:

As for the butterfly logo: most of us grew up learning about the wonder of metamorphosis and how incredible beauty can often evolve from plain or even ugly beginnings. We chose the blue morpho butterfly as the icon for Story Arts Media because it is the perfect symbol for such transformation of content. We also fancy this impossibly gorgeous fellow because, like many creative types, he lives life large and is a bit of a hedonist. Subsisting only on the juice from fermented fruit, our sometimes slightly inebriated mascot is still a highly skilled flier capable of out-maneuvering even predatory birds. He is rare and highly coveted – not unlike truly good media.

In hindsight I realized that my beautiful blue-winged wonder would also make a great statement on a bottle of wine. What example of metamorphosis is more profound than simple grape juice turning into wine?! And so a brand was born.

As weeks turned into months and I eventually finished—and survived—making the Tiny Vineyards film, everything slowed way down. I mean way down. And it dawned on me that wine was truly the ultimate “slow food.” I mean, come on, what food or drink product do you consume that takes a minimum of two to three years to prepare?!

The problem is that I’m not a particularly patient person and it sometimes drove me a little crazy waiting to see what my first wines would become. But wait I did, mainly because I had read somewhere that the oak flavor imparted by aging wine in barrels would actually mellow over time. And I had two wines that needed some major mellowing.

Fortunately there were all kinds of distractions to help keep me from obsessing over the outcome of my first winemaking effort—two new documentary film projects that required a lot of travel, an actual vineyard to construct and plant for a friend (story to come), and a second vintage to consider (story also to come). But underneath it all was the totally lightweight yet undeniable concern whether I would even want to keep making wine if my first effort was a failure.

Finally, it was October 2019 and the time was nigh to bottle my wine. I had been racking and making the requisite sulfur additions throughout the year and, of course, tasting it each time I opened up the carboys. But almost eight months passed before I noticed any real development in the wine, and a heady aroma of vanilla still prevailed. A little softer maybe, but quite noticeable. The amazing thing, though, was that both my Cabernet Sauvignon and my wacky field blend were actually starting to, dare I say, taste kind of good!

Bottling was fun, and totally amateurish with my little bottling wand and mouth-powered siphon. But I ended up with 25 bottles each of my two kinds of wine, to which I promptly applied labels and color-coordinated heat-shrink capsules (cork coverings). It was an incredible feeling seeing those professional-looking bottles of wine that I had made all by myself (with significant guidance from a few fellow enologists) all lined up on the patio table.

I gave away almost all of that first vintage to friends and family, with the pleading admonishment to “let it age for a year or so and it’ll be so much better.” Both wines had continued to mature, but I was frankly really embarrassed by my rookie over-oaking. Nevertheless, a few folks opened it early and responded positively. Knowing that your friends will tell you what you want to hear—and bless ’em for that!—I needed an impartial opinion. So, I decided to enter the wines into two big contests. Talk about chutzpah!

The first was the U.S. Amateur Winemaking Competition put on by Cellarmasters in Los Angeles. The deadline for entry was almost immediately, with the final results announced in mid-November. The second contest was the 2020 WineMaker Magazine International Amateur Wine Competition with a March 2020 deadline for entry, and final results announced in June. I figured that, with at least the second competition, my wines would get another almost six months to age—which was a very good thing. That positive handicapping increased significantly with the onset of COVID-19 and the repeated delay of the judging, which finally occurred almost an additional six months later in August.

So what was the final outcome?

Pure magic! And probably way more than deserved, given the luck behind these two wines. Drumroll…a silver medal for the Cabernet Sauvignon from Cellarmasters and a gold medal for the Red Field Blend from WineMaker…drop the mic.

Guess I’ll make a second vintage.

👏🏼👏🏼👏🏼👏🏼👏🏼👏🏼👏🏼💕💕💕💕💕