There is a comfort in rituals, and rituals provide a framework for stability when you are trying to find answers. —Deborah Norville

True stability results when presumed order and presumed disorder are balanced. A truly stable system expects the unexpected, is prepared to be disrupted, waits to be transformed. —Tom Robbins

The relief of the season’s first racking

Winemaking is fraught with disquietude. It can only be considered, by its very chemical nature, as barely controlled chaos. And so, I wish to coin a phrase as it relates to finding calm within this storm of uncertainty, and that is—Point of Stability.

It happens for me every vintage when we first rack the new wine, which was just this past Tuesday this year. All my grapes from the 2022 harvest have taken their journey from the vineyard to the crush pad, where they were weighed, sorted, dumped into the de-stemmer and crushed according to the varietal and style of wine I hoped to make. At that point they are called must—mashed grape pulp, juice, skins, seeds and occasional stems. The must is then poured into an open one-ton fermenter and combined with dry ice pellets, most likely a small dose of sulfur dioxide (SO2) to vanquish any microbial baddies, maybe a tartaric acid addition if the pH is too high and the titratable acidity too low, and—dare I say— maybe even a watering back if the Brix is too high. It is then left to cold soak for a day or two. I did this over a dozen times this year.

Then, if I’m feeling brave, I do nothing. I wait for Mother Nature to do her thing. If I woke up that morning feeling a little freaked out by the thousands of dollars I invested in every one of those fermenters, then I don’t take any chances with native fermentation and I inoculate the must with some form of commercial yeast. In either case, I wait—and wait—usually for two or three days until measurements taken each morning begin to reveal an increase in temperature and a drop in sugars. My anticipation is then further rewarded, I hope, with physical evidence that primary (alcoholic) fermentation has begun—bubbles on the surface of the must, a faint “snap, crackle and pop” (if the winery isn’t blasting its omnipresent Spotify), the formation of a thickening “cap” of grape parts at the surface, and a shocking yet very welcome waft of sharp, acidic CO2 when I pull back the plastic cover of the fermenter to do an olfactory check.

That onset of primary fermentation is both my first relief and the beginning of my next anxiety. Okay, we made it this far, but will the fermentation complete itself and get to dryness? Or will it stall out—maybe even get stuck!—requiring a dreaded restart? Am I properly punching-down and/or pouring-over, extracting enough goodness—phenolics, flavonoids, esters, tannins—from the must? Or is the developing wine becoming bitter or reductive, or thin and flabby?

The list of possible pitfalls is long and always present, as is my worry. And I don’t begin to relax until every fermentation is finished, the new wine is pressed, tasted, and deemed ready for barreling. Even then, things aren’t yet stable. This new vintage, no longer protected by its layer of CO2 in the fermenter, is now susceptible to oxidation and possible spoilage organisms, and it needs to go through malolactic fermentation (MLF) before it can be considered truly stable (you got an earful from me about that in my late December post). This secondary fermentation—defined as the conversion of malic acid to lactic acid— is usually natural and spontaneous, but it can take two or three months to complete. Any attempt to jump the gun on stabilizing the wine, by adding SO2 or lowering the temperature, only prolongs the effort.

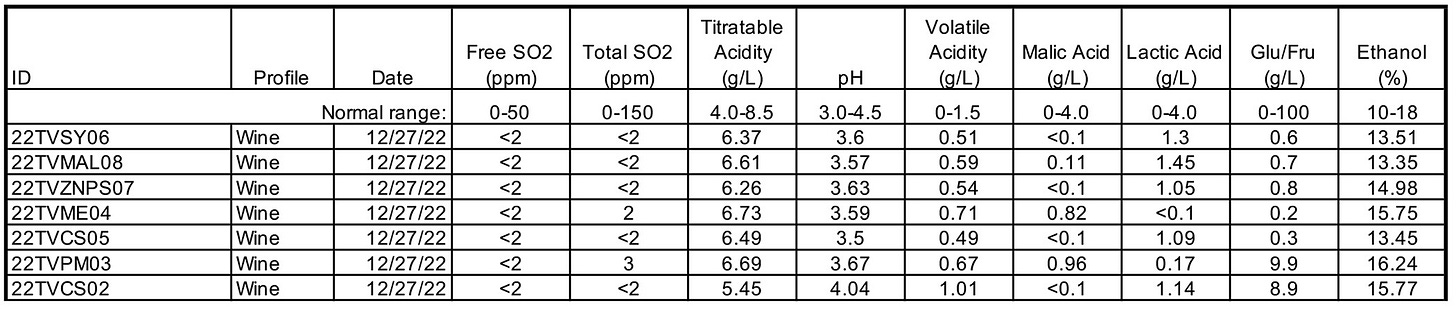

So here we are, three to four months after all my alcoholic fermentations have finished, and MLF is probably complete in them as well. But to be sure, it’s back to the lab. This time for a “wine profile panel.”

This is where chemistry is your friend. In fact, it’s your salvation. Pay attention, grasshopper! You can see in the panel above that, with two exceptions, all of the wines are indeed through MLF, each now containing less than a tenth of a gram per liter of malic acid and well over a gram per liter of “new” lactic acid. Go back up to the Malbec sample (22TVMAL08) in the must profile panel near the top of the page. You can see that as fresh juice it had 2.07 g/L of malic acid, and now, as wine (22TVMAL08), it has less than 0.11 g/L of malic acid but 1.45 g/L of lactic acid. MLF darn near complete. Pretty cool, eh?

So bear with me. This might get a little technical but hopefully it will also be enlightening. There are a LOT of other VERY important revelations to be found in these chemical analyses. Ones that will surely help to ensure the best possible wine outcome if acted on accordingly. Those aha moments are that:

Four of these wines (Syrah-22TVSY06, Malbec-22TVMAL08, Cabernet Sauvignon-22TVCS05, and the Zinfandel/Petite Syrah/Mourvèdre field blend-22TVZNPS07) require no additions or adjustments other than a protective dose of SO2. These four wines were all in good chemical balance at the end of primary and secondary fermentations, with optimal pH and titratable acid levels—due to good vineyard practices, attaining genuine ripeness and nailing the correct harvest dates, and proper adjustments at fermentation. An example being a rather aggressive addition of tartaric acid when we noticed our Malbec grapes coming in at harvest with abnormally high levels of potassium, which had severely increased the pH and destroyed the acid (see must profile panel with Malbec sample at the top of page). Of course all of this supposed winemaking mastery could also be attributed to good old dumb luck. So much of winemaking is just that!

Three of these wines have very high alcohol levels (Merlot-22TVME04 at 15.75%, the Primitivo/Tannat field blend-22TVPM03 at 16.24%, and the other Cabernet Sauvgnons-22TCAS02 at 15.77%)—due, no doubt, to high harvest Brix from the heat dome we suffered during harvest.

Two of these wines, the Merlot (22TVME04) and the Primitivo/Tannat field blend (22TVPM03) have yet to go through MLF—check the ratio of malic acid to lactic acid!—likely due to the higher alcohol content.

One of the Cabernet Sauvignons (22TCAS02) is out of balance with a pH that is too high (4.04) and a titratable acidity that is too low (5.45 g/L)—due, we know, to a very young vineyard being thrown way out of balance by the heat dome.

That two of these wines, the Cabernet Sauvignon (22TCAS02) and the Primitivo/Tannat field blend (22TVPM03) are actually not totally dry yet (haven’t finished primary fermentation) with residual sugars (Glu/Fru) readings of 8.9 g/L and 9.9 g/L respectively—due again to high alcohol-caused yeast mortality.

Wow! How would I have ever known any of this without that wine profile panel? Some of the old-timers claim to be able to taste such anomalies, and I don’t doubt that they can. But my palate has certainly not developed (yet!) into that sophisticated of a tool. To borrow from an old marketing slogan, “Better wine through chemistry.” And I don’t mean covering up wine faults with multiple chemical additions. I mean fixing wine faults through minimal but necessary natural intervention, guided by chemical analysis.

So we moved all 26 barrels of our 2022 Vintage out onto the winery floor (above)—it was a beautiful sight!—and proceeded with our first racking. Racking is simply pumping wine from its original barrel into a tank, cleaning the barrel of any leis (sediments) that have fallen out of solution and built up on the bottom, and then pumping the wine back into the barrel—along with any additions or adjustments you might have made in the tank. This also helps the wine to clarify, and releases malodorous volatile sulfur compounds like hydrogen sulfide (H2S).

First, we racked the four wines that needed the least attention (Syrah-22TVSY06, Malbec-22TVMAL08, Cabernet Sauvignon-22TVCS05, and the Zinfandel/Petite Syrah/Mourvèdre field blend-22TVZNPS07), and while they were in the holding tank I added enough potassium metabisulphite powder to establish a .05 ppm molecular SO2 level—the amount recommended to protect red wine against microorganisms and unwanted bacteria. SO2 occurs naturally in wines and the addition of minimal amounts for microbial protection is acceptable to all but the most diehard natural winemaker. Then we pumped these wines back into their barrels and replaced their permeable fermentation bungs with long-term hard bungs to seal out oxygen. They were good to go.

Then we addressed our three “problem” wines (Merlot-22TVME04, Cabernet Sauvgnon-22TCAS02, and the Primitivo/Tannat field blend-22TVPM03). Since our plan is to eventually blend the Merlot with the Primitivo/Tannat field blend we watered back each wine by a gallon a barrel to see if we could lower their high alcohol content a little and perhaps stimulate MLF (and maybe even primary fermentation in the Primitivo/Tannat). We also held back any SO2 addition for the same reasons. I’ll monitor these two wines carefully over the next few weeks and if I don’t see any further evidence of secondary fermentation I’ll likely inoculate them with Oenococcus oeni, the bacteria responsible for MLF.

As for the Cabernet Sauvignons (22TCAS02), we gave it a half-dose of SO2 to provide a little protection, but not enough to prohibit it from finishing off primary fermentation. We further sought to stimulate that, and bring the wine back into balance, by adding enough tartaric acid to drop the pH back down into the 3s and increase titratable acidity to somewhere around 7 g/L. As for the high alcohol content, we plan to blend this Cab, which is currently at 15.77% with some Cabernet Sauvignon-22TVCS05, which is currently at 13.45. I did a quick bench trial of various combinations and there’s a real winner in there!

So, did I reach a Point of Stability? Yeah, I think I did. I find it satisfying to be proactive, to fix things. I find it calming to occupy that stable space—that Tom Robbins describes in his quote at the top of the page—between disruption and transformation. That’s how I’m now finding winemaking. Obviously, there’s still a lot I have to keep my eye on, but I feel at least somewhat in control knowing that four of our wines have been formally tucked in and put to bed for the winter. The other three? Well, like the children they are, they may need a back rub, or another story book, or I may need to keep the light a little longer. But they’ll all soon be asleep as well.

As will I.

Speaking of stability…

This Monday, January 9, marks the start of my final course in the UC Davis Winemaker Certificate Program. I’m actually unhappily on the waiting list, but I’m hopeful a space will clear and I’ll be able to take Winemaking Stability and Sensory Analysis and finally earn my certificate after two long years of study and instruction.

The subject of this final course is somewhat apropos of where I am as a winemaker, as three months from now I will be bottling our first commercial vintage. In the course, according to their syllabus, we will be introduced to the science involved in controlling wine stability in bottled wines. We’ll explore various methods for testing and controlling wine stability including: filtration, bitartrate stability, protein instability, metal stability, fining agents, and oxidative and hydrolytic enzymes. We’ll learn the basic anatomy and physiology of the human organoleptic senses as they influence our interaction with wine, and we’ll be introduced to basic sensory science analyses, such as component recognitions tests, discrimination tests, paired comparisons and triangular tests.

By the end of this course, they’ve promised we’ll have an effective competency in the theory and practice of wine analyses and processes in order to produce a stable wine product for the marketplace. Well, geez, that should be worth the price of admission, if only I can stay awake!

Joe--

I have a few disclaimers.

One: those of us playing the fourth quarter reliably turn the theory of how one's primary characteristics become more extreme as they age, into reality. For instance, I have never been a very patient person. These days, my impatience has gotten dangerously high, especially while driving. My keepers have removed the Glock from the glove compartment.

Two: I'm not sure I have ever read any "wine writing."

Three: I am not a wine enthusiast, although under the tutelage of experts, yourself included, I have tasted some delicious wines.

Four: the only reason I didn't fail high school chemistry is because the 70 year-old teacher had never failed anyone, and he was goddamned if I were going to break his record.

Having said all that, I have to remark on the highly technical trending of your Tiny Vineyard reports. I'm sure you know your audience, part of which must be at least amateur wine makers who are taking notes and trying to relate. But the preponderance of chemistry and other murky details send me into a spin. It's a good idea to allude to the massive complexity that's involved in your craft just so readers can bless you for bearing that daunting weight, appreciate the miracle involved with making a tasty product, and be willing to pay handsomely, and with heartfelt gratitude for the delicious varietals you offer so reasonably. But the mind-blowing amount of tech you include in the reports reminds me of my first and only day in Economics 101. We sat there while the grad student teacher never said so much as hello or anything else for the fifteen minutes it took him to cover thirty feet of blackboard with an endless formulaic progression. When he was done, he looked up, brushed the chalk off his hands, and said: "any questions?"

I got up and left at that point, went to the drop and add office, then bought a bottle of wine.

Roger (friend and collaborator)

7199 Frances Street

Easton, Maryland 21601 U.S.A.

410-822-3946 cell: 410-353-7545

www.rogervaughan.net