If you run, you are a runner. It doesn't matter how fast or how far. It doesn't matter if today is your first day or if you've been running for twenty years. There is no test to pass, no license to earn, no membership card to get. You just run. — John Bingham

Get a job

I remember when starting a small business was as uncomplicated as simply hanging out your shingle and announcing your intentions — butcher, baker, candlestick maker. For many of us our first experience making money (not supplied by our parents) was a simple kid-size job like shoveling walks in the winter, raking leaves, mowing lawns, taking care of the neighbor’s pet, or maybe having a paper route. Then came a succession of part-time and summer jobs as we matriculated through high school and college. I was a stock boy at a department store, a dishwasher, fry cook, flower delivery boy, mountain trail builder, animal caretaker at a university laboratory, construction laborer, drywall hanger, ski instructor, hasher (waiter) at a sorority house, freelance photographer, wooden spinning wheel maker, patio deck installer, and offset press operator.

These were, for the most part, okay jobs — but menial. Yet they served the purpose of developing increasing levels of financial freedom and personal independence. I liked to work as much as I liked to play, but I learned from early on (perhaps too early) that I didn’t like “working for the man.” I wanted to own the company, be the boss, make the decisions, garner the riches.

As a Colorado native I was able to attend the University of Colorado for about $3,000 a year. My dad would send me $1,500 a semester for tuition and I was expected to get a job to cover the rest of my expenses. Of course, I inevitably spent my dad’s check on a season ski pass and/or some new skis, or a used motorcycle, or a new camera. That left the original tuition still unpaid, along with food and rent. So quite quickly, and out of increasing necessity, my first self-employed venture was conceived. My shingle read, “Daniel Firewood Company.”

As every entrepreneur knows, success comes from recognizing and leveraging an opportunity. At the time, I lived in a tiny cabin up Boulder Canyon about six miles from town. My rent was nominal — $70 a month. I owned a 1959 International Harvester Travelall 4X4 truck that could haul anything, and a collection of discarded heavy hand tools I’d scavenged from various construction jobs and refurbished, including an axe, a maul, several steel wedges and an old chainsaw.

The “opportunity” was a pine beetle infestation that had wreaked havoc on many of the Canyon’s tall ponderosa pines. Dead trees were pretty common, and the Forest Service encouraged their removal. The only real challenge was finding a tree close enough to a road so that once I felled it and bucked it into fireplace-size lengths I could get them to my truck without too much effort.

And that’s what I did every summer and fall throughout college, whenever I needed money. I’d drive the cut-up logs back to my cabin and split them by hand before loading them back into my Travelall and delivering them to a customer. I could get around $60 per cord of wood, and I could hand-split a couple of chords in a day. It was hard work but unfailingly constant, and in many ways the perfect job. And at no time did I need a license or permit to operate.

Jump ahead 50 years. The game is far from over, but I might concede that I’m getting near the end of the third quarter. I’ve remained entrepreneurial ever since I established the Daniel Firewood Company’s World Headquarters in Boulder Canyon. I built a large portfolio (Story Arts Media) of freelance projects and stand-alone businesses mostly centered around media and the creative arts—photography, design and production, writing and editing, magazine publishing, direct marketing, book packaging, television producing and documentary filmmaking—with a few errant forays into selling adventure fly fishing travel, promoting buffalo meat over beef, and inventing the best barbecue sauce on the planet.

Most of these ventures were successful, at least to a degree, but some decidedly not. Yet again, I never encountered insurmountable barriers to entrance or excessive governmental control. If I failed at something it was usually my own fault—I’d come to the party too late, or hadn’t done adequate due diligence, or had simply let curiosity and passion push me into the deep end without really knowing what something was about.

Wait a minute… don’t those faults literally define my immersion into winemaking? And add back in some very real barriers to entrance and some ridiculous government control, and… maybe I should be rethinking this whole thing.

Operating a wine company in California is a highly regulated activity subject to obtaining the required licenses and permits from the Federal Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau (TTB), and the California Department of Alcohol Beverage Control (ABC). Selling your wine to certain states outside of California further complicates things, sometimes to the point of impossibility. To understand why this labyrinth of bureaucracy exists we have to go back 90 years to the final days of Prohibition.

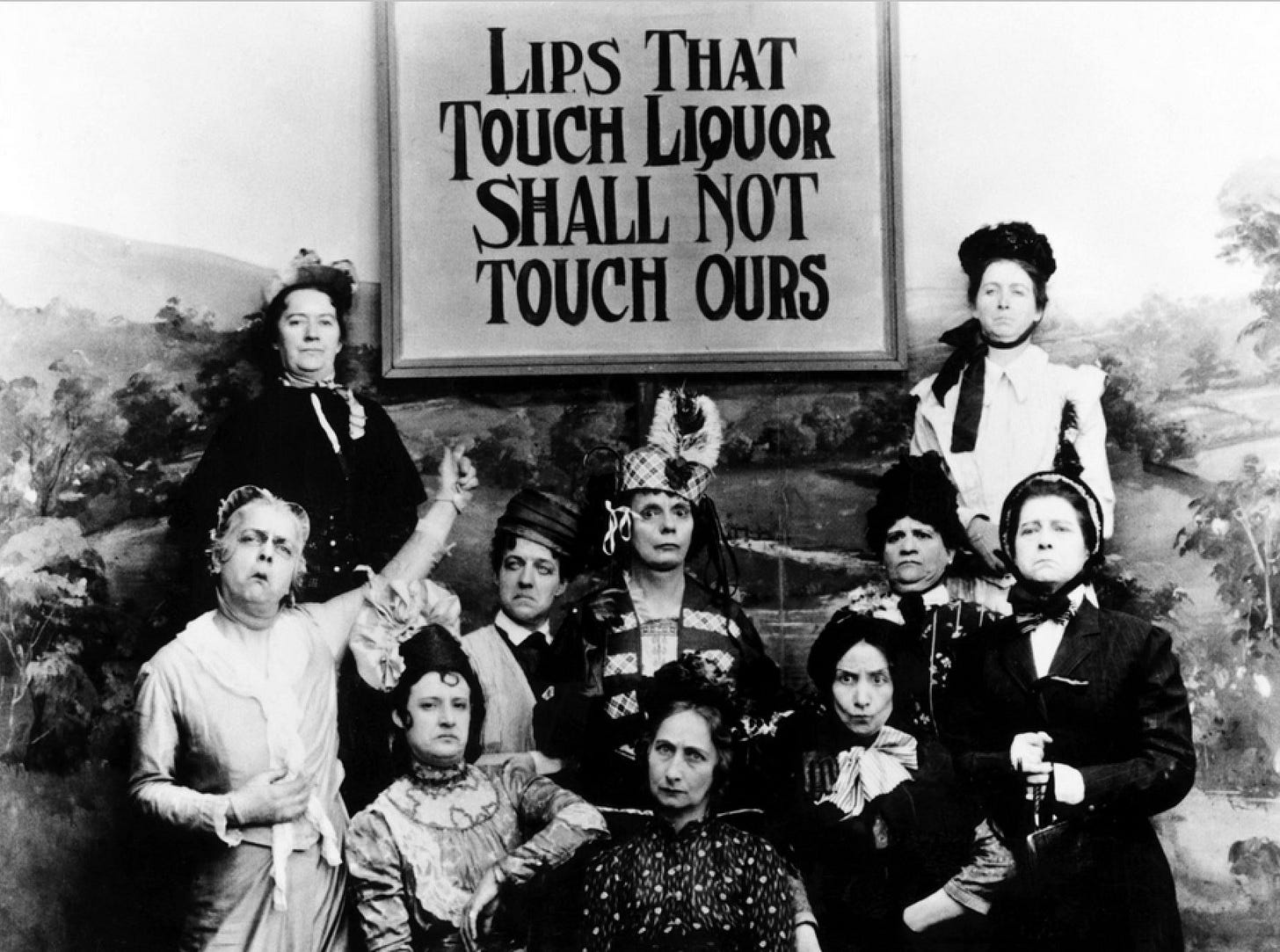

To borrow and summarize from Wikipedia: Prohibition was a popular nationwide constitutional law ratified by the Eighteenth Amendment. It strictly prohibited the production, importation, transportation, and sale of alcoholic beverages in the United States from 1920 to 1933. Despite the positive social changes brought about by Prohibition—and there were arguably many—the legislation would not survive.

Prior to Prohibition’s implementation in 1920, the nation suffered epidemic levels of alcoholism, head-of-household truancy causing familial and social discord, and cirrhosis-driven health concerns. Most citizens agreed, things had to change.

Yet approximately 14% of federal, state, and local tax revenues were derived from alcohol commerce. When the Great Depression hit and tax revenues plunged, the governments needed this revenue stream. The shocking $11 billion of lost tax revenue, and the estimated $300 million needed to enforce Prohibition, was too much for the nation to withstand. Farmers, who had fought for Prohibition, now fought against it because of the negative effects it had on the agriculture business. Economic urgency played a large part in accelerating the advocacy for repeal.

On March 22, 1933, President Franklin Roosevelt signed into law the Cullen–Harrison Act, legalizing beer with an alcohol content of 3.2% and wine of a similarly low alcohol content. Subsequently on December 5, ratification of the Twenty-first Amendment to the United States Constitution repealed the Eighteenth Amendment—the first and only Constitutional amendment ever to be repealed.

The Twenty-first Amendment grants each state and territory the power to regulate intoxicating liquors within their jurisdiction. As such, laws pertaining to the production, sale, distribution, and consumption of alcoholic drinks still vary significantly across the country today.

The Amendment does not prevent states from restricting or banning alcohol; instead, it prohibits the "transportation or importation" of alcohol "into any State, Territory, or Possession of the United States" "in violation of the laws thereof,” thus allowing state and local control of alcohol. There are still numerous dry counties and municipalities in the United States that restrict or prohibit liquor sales. Additionally, Federal law also prohibits alcohol on Indian reservations, although this law is currently only enforced when there is a violation of local tribal liquor laws.

An interesting aside: It was never actually illegal to drink alcohol during Prohibition—just to make it, transport it, and sell it commercially. But the government allowed any man to make up to 200 gallons of wine a year at home for personal use. This same law still governs amateur home winemakers today. However, during Prohibition federal law prohibited the manufacture of distilled spirits even for personal use, and has continued that restriction today for anyone not meeting numerous and impractical licensing requirements.

So where does all of this leave someone like me, who is simply wishing to sell my wine to folks wanting to buy it? Dazed and confused, I’d say.

For those who want to delve a little further, let me set the stage.

According to Congressionally enacted Public Law 95-458 (H.R. 1337), and pursuant to the California Business and Professions Code §23356.2 — If you are an amateur home winemaker in California no license or permit shall be required for the manufacture of wine for personal or family use, and not for sale, by a person over 21 years of age. The aggregate amount of wine with respect to any household shall not exceed (1) 100 gallons per calendar year if there is only one adult in the household or (2) 200 gallons per calendar year if there are two or more adults in the household.

Wine produced pursuant to this section may be removed from the premises where made only under any of the following circumstances: (1) For use, including in a bona fide competition or judging or a bona fide exhibition or tasting. (2) For personal or family use. (3) When donated to a nonprofit organization… for sale at fundraising events conducted solely by and for the benefit of the nonprofit organization. Wine donated pursuant to this subdivision may be sold by the nonprofit organization only for consumption on the premises of the fundraising event, under a license issued by the department to the nonprofit organization pursuant to this division… and shall bear a label identifying its producer and stating that the wine is homemade and not available for sale or for consumption off the licensed premises.

And it goes on and on from there. Bottom line is you may not sell any of the amateur wine you make. Technically, you’re not even supposed to give it away for free to anyone beyond your own family members. So, if you want to start a commercial wine company and sell your juice, you’ve got to become a “pro.”

When I first started looking at what it would take to legally sell my wine, there were really only two options that made sense:

1) Type O2 Winery or Winegrower License*

This is the most central license held by most bonded wineries in California. It allows you to make wine, sell it direct-to-consumers (DTC) online or through a club by phone or direct mail, or to a wholesale distributor, or direct to retail outlets like restaurants, grocery stores or wine shops. It allows you to sample and sell your wine DTC on your own premises and/or at an off-premise tasting room. It also allows you to sell and ship your wine DTC, or on a wholesale distributor basis, to any state in the country pursuant to the laws of each state.

The downside is in that word “bonded,” which means the winery must comply with all city, county and state laws governing the infrastructure and operation of a legal facility for making wine, including environmental impact, waste water remediation, OSHA requirements, public access, etc., etc., etc. Add to all of that the original cost of the land, the materials and construction expenses of the facility, and then outfitting it with all the specialized machinery and equipment necessary to make wine. I have a friend in the midst of everything described above and he’s approaching a million bucks in expenses—even though he already owned the land.

2) Type 17 and Type 20 Wine Licenses Combination*

According to Wine Direct, “The last decade has seen an explosion of what have become to be known as virtual wineries.” This hip, progressive name is generally applied to winemakers who hold a combination of a Type 17 Beer/Wine Wholesaler license and a Type 20 Off-Premise Beer/Wine Retailer license. Licensees focus on selling direct to consumers through online websites. The Type 17 license also permits “incidental sales” to other supplier-type licensees (like distributors and retailers). However, to qualify as a bona fide wholesaler, a licensee must sell to retailers generally.

The 17/20 license combination is a relatively inexpensive way to enter the industry because it does not require the holder to purchase equipment or have their own bonded wine production facility. Holders have their wine made at someone else’s 02 licensed and bonded winery (often referred to as “custom crush”) and don’t take ownership of it until it is bottled and excise taxes are paid. For small producers, this license combination allows them to avoid the cost, overhead, and liability associated with owning and operating a licensed, bonded, winery, while still being able to sell that wine to consumers, wholesalers, and retailers. Many fine wines are being made by virtual wineries and it has been a tremendous boon to the growth of the industry.

There are a few major drawbacks to a 17/20 combination license for a winemaker in California. First, 17/20 licensees cannot have a bricks-and-mortar facility that the public can visit, and cannot offer tastings to consumers—a tried and true method for selling wine and building a future customer base and club memberships. And second, licensees can only sell and ship their wine inside of California, and to only 13 other states in the country—further limiting sales, and requiring careful compliance adherence. And third, 17/20 licensees do not have wine production rights. As previously mentioned, they pay a fee to have their wine produced at a licensed winery’s bonded wine facility. That fee covers the use of the that facility, all the wine making equipment, and the personnel to actually make the wine. It doesn’t cover the cost of grapes, barrels and bottling. Licensees do not take title to the wine until excise taxes are paid and the bottled wine is removed from the bonded facility by the 02 licensee. This can certainly have a limiting effect on personal styles of winemaking.

Epiphany

Of course, I wanted to be as fully licensed as possible, operate out of my own bonded winery facility, and maybe even feature a small estate vineyard when I formed the Tiny Vineyards Wine Company. But I also dreamed about creating a self-financing, one-man micro winery that produced a maximum of 1,000 cases a year. The two were not mutually exclusive, but the latter scenario was far more realistic when faced with the economic realities of creating a wine enterprise today in Sonoma, California. So, somewhat disappointedly I opted for entering the industry with a 17/20 combination, while hoping to one day grow into the big boy license.

That remained my intention as I declared my commercial conversion back in June of 2021. I then operated under that 17/20 designation for over a year until September 1, 2022 when I met with Jack Sporer, the co-founder and director of Magnolia Wine Services (where I make my wine), to seek guidance in completing my 17/20 application. I wanted to make sure I was properly licensed before my first vintage wines were ready to release in early 2023.

“So you still going with a 17/20, or are you going to get an O2 license?”

“I can’t afford to get an O2 license. Wouldn’t I need to also be a bonded winery?”

“Yeah, but you can do it here as an AP.”

Winemaking is already full of way too many acronyms to try and quickly decipher another one while feigning you know what it means.

‘What the hell is an AP?”

“You don’t know what an AP is? Oh dude…”

The Federal Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau (TTB) regulations permit a winegrower to use the facilities and equipment of another winegrower to produce wine. This is commonly referred to as an AP, or “Alternating Proprietorship.” In the Alternating Proprietorship model, separate 02 licenses are issued to each legal entity manufacturing wine under a single bonded winery permit.

Whoa Nellie! Stop the presses!

And just like that my winemaker future took flight. I quickly jumped ship from becoming a 17/20 combination license holder to becoming an O2 licensee operating as an AP under Magnolia’s bonded winery permit.

Sure, the application is a bit more onerous and expensive than a 17/20 application, and unless you commonly navigate through reams of legalese you really should use the guidance of a compliance attorney when filling out and submitting all the forms—and there are a lot of them. You need to get a Basic Permit from the Federal Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau (TTB)—and the Feds will do a background check on you—and a Winegrowers License from the California Department of Alcohol Beverage Control (ABC). You need to publicly post notice for 30 days of your application to sell alcoholic beverages, and you need to get a Seller’s Permit from the California Department of Tax and Fee Administration.

You’ll also need to do a healthy amount of reporting each quarter and annually. And you’ll need to get serious about compliance with the myriad regulations governing the wine industry on a national level, within California, and within every other state you hope to do business with. But if you do those things, you’ll actually get to do business, at the highest level allowed by law. Getting that O2 license in an AP partnership with Magnolia was an instant no-brainer for me.

I connected with Lana Coil at Silver Key Legal, an attorney Jack recommended, and she was simply fantastic—not to mention extremely reasonable in what she charged new winemakers just starting out. I had everything she requested to her by October 1 and she had all the applications filed a week later.

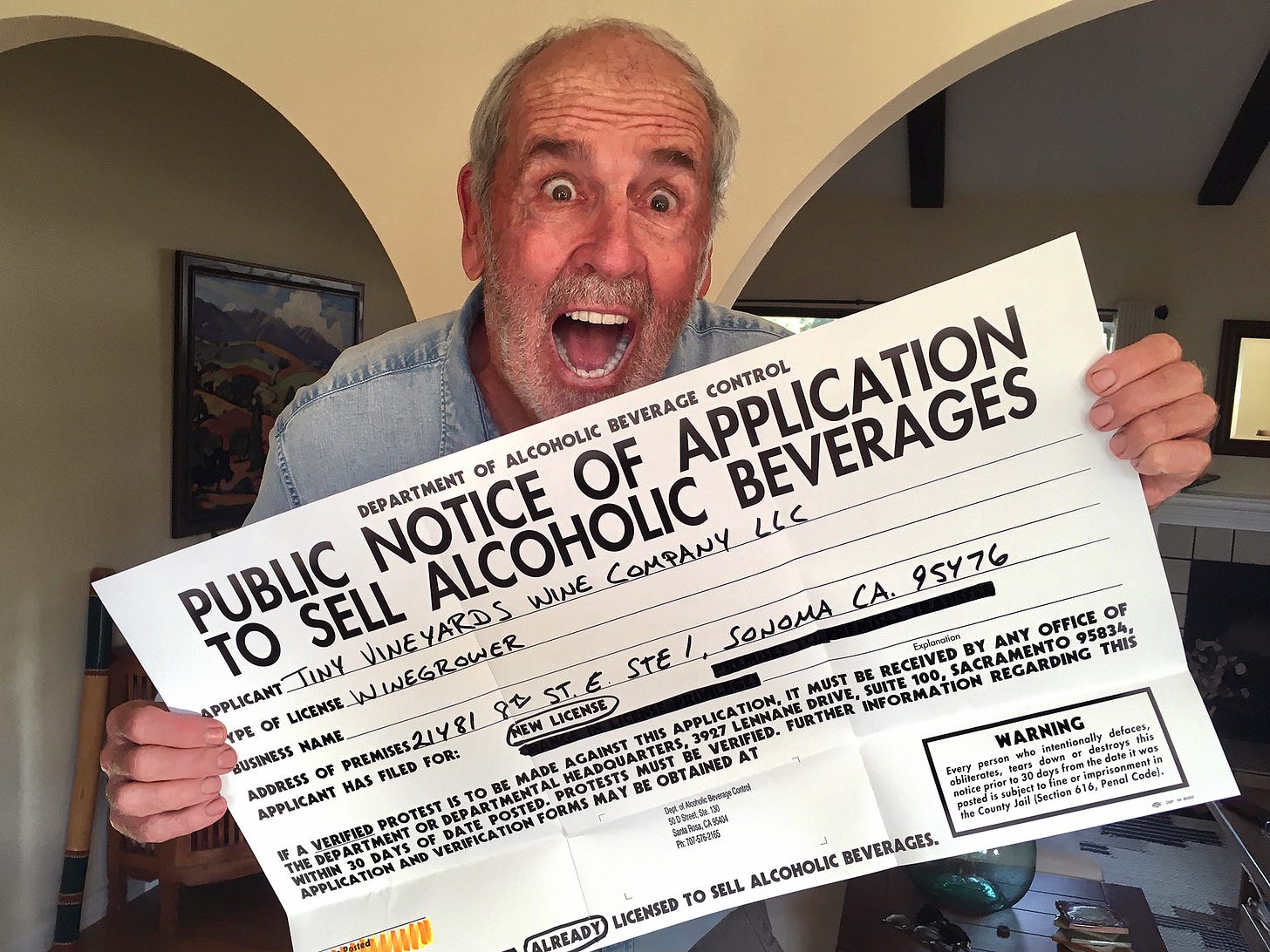

I posted my oversized Public Notice of Application to Sell Alcoholic Beverages on Magnolia’s front door on October 17th and no one saw reason to protest it during the following 30 days.

Nothing showed up on my background check (whew!) and I had my basic Federal Permit from TTB in hand on November 17th.

I received my Seller’s Permit on November 22nd.

And I had my bright pink Winegrower’s License from ABC on November 29th.

Now, onward… to the stars!

*Thanks to Rogoway Law Group and Wine Direct for interesting online discussions on wine licensing.

Check out our Advance Case Sale

Thanks to everyone who has already reserved an allotment of our 2021 inaugural vintage wine! If you haven’t yet had the opportunity, visit our Advance Case Sale today. These are the wines you been reading about here in this newsletter for the past year and a half, and they are terrific. And, with discounted cases and half cases—and FREE SHIPPING!—this will be the best deal offered, probably forever.

Please consider this: Good winemaking requires so much time in handcrafting and aging that it's literally years before we see any financial return on a specific vintage. Your support in this advance sale helps us immensely in bridging the gap between vintages. But don’t delay. The entire 2021 vintage will be fewer than 300 cases and it will surely sell out quickly once released to the public and our retail distributors.

We’ve built a simple, secure online storefront that allows you to purchase and reserve a case or half-case of each varietal, or all three together. Please check it out right now at: tiny-vineyards-wine-company.obtainwine.com. And, be sure to click on the individual bottles for some previously untold stories about the wine.

A sincere thank you for your support!