Wrapping up the year

Reflection, production class over, MLF chromatography, penny fix, falcons, biplanes and glorious rain!

Year’s end is neither an end nor a beginning but a going on, with all the wisdom that experience can instill in us. ― Hal Borland

Life can only be understood backwards; but it must be lived forwards. ― Søren Kierkegaard

A sober soliloquy for the holidays

I wavered on including these thoughts as this newsletter is meant as a journal, not a soapbox. But year’s end is a time for reckoning and reflection, and the increasingly tenuous nature of our relationship with our planet and with each other demands that voices be heard, however hesitant or tongue-tied they might be.

During this past year the world often wobbled sickeningly off axis and we all held our breath, again, and again. It has been a period of uncertainty underscored by disbelief. We voted in redemption but were shocked by insurrection. We found social justice but balked at transformation. We dodged fires in Sonoma—not elsewhere—but suffered record-breaking drought, while folks to the east drowned in floods, and died in tornados. We beat Covid-19, but then we didn’t. We broadcast climate change around the world, but it felt like crying wolf.

I don’t like being a harbinger of doom. It’s just not in my nature. I’m an optimist and subscribe to the eat, drink and be merry credo. Isn’t that the reason for wine?

But after the past two years I venture into 2022 a bit disquieted, hoping to still find solace in the natural order of things—the promise of winter dormancy, spring resurgence, summer growth and autumn harvest. I seek a farmer’s life, a cook’s bounty, an artist’s eye, a lover’s touch, a winemaker’s knowledge, and a storyteller’s courage. Is that too much to ask? Is it too little?

We simply must stop, right now people, and pull ourselves together—as a nation and as a world—or else risk our very humanness. Our entitled existence on this beautiful planet is still on a trial basis at best. Let’s not continue to screw that up. As my old man used to punctuate the end of every stern lecture, “‘nuff said.”

Three down, three to go

Just finished my Wine Production course, the third one I’ve taken towards earning the Wine Making Certificate from UC Davis—and my “spare” time torment during the entire two months of harvest. It was definitely challenging at times to crack open that six-and-a-half-pound tome of a textbook and read the assigned pages of very dry, literally sleep-inducing scientific writing set in 8pt type when all I really wanted to do was… anything else!

And yes, there was that frustrating timing issue of learning about wine production while you were actually doing wine production in real life, only you were a little bit ahead of the syllabus. It was repeatedly exasperating to learn how to properly do something production-wise—like design a style-specific punch-down protocol, or conduct simultaneous alcoholic and malolactic fermentations—just a week or two after you’d done it all wrong with your own production. [Note to anyone considering this course in the future: Take it in the summer quarter if you can, especially if you’re processing grapes that fall.]

But that said, and my tiresome carping aside, I loved the course and really learned a lot. Even managed to score an A (probably because only one mathematical equation question ever appeared on a test!) and kept my streak alive. And, despite the timing misalignment described above, it really couldn’t have come at a better point in my winemaking trajectory. This was information and technique I could really use, and needed to adopt if I was ever going to cross that line from home sorcerer to professional winemaker.

Next class, Viticulture, beginning January 3, 2022—also good timing (I hope!) as I have two small vineyards entirely dependent on my stewardship this year.

Putting it all to practice

Okay, so bear with me a moment. This is cool stuff.

Red wine generally goes through two fermentations, the one everyone knows about—alcoholic fermentation—where the sugar in the grape juice is converted to alcohol by hungry Saccharomyces cerevisiae yeast; and the lesser-known event—malolactic fermentation—where the malic acid in the wine is converted to lactic acid by hungry Oenococcus oeni bacteria. There’s a lot of chemistry going on here, but suffice it to say, both are essential in their own ways for producing big, rounded, complex red wines with soft tannins, lively acids and good mouthfeel. So it should go without saying that as a winemaker you want to make sure your wines have successfully completed both fermentations before you bottle them.

In the home-winemaking world we tend to initiate and complete the alcoholic fermentation reasonably well by inoculating with commercial yeast shortly after we de-stem and crush our grapes. But not everyone pays attention to malolactic fermentation—or MLF, as it is known—or is even aware of its existence, as it often starts on its own from feral lactic acid bacteria living in the winery or in previously used barrels that have held wine that went through MLF.

But in the commercial wine world, MLF is very controlled and is usually simultaneously or consecutively initiated around the same time as alcoholic fermentation. The reason for this is simple. Lactic acid bacterias and fermentation yeasts are both very sensitive to sulfur and to colder temperatures. Most alcoholic fermentations are inoculated with commercial yeast while it is still relatively warm in the cellar, and hence they successfully come to completion ten days to two weeks later. But MLF can often be slow to start on its own and even slower to finish if colder weather arrives. It’s not uncommon for MLF, particularly in homemade wines, to take a long snooze during the winter months and not complete until it warms up the following summer.

But that doesn’t work for most commercial winemakers. They want to add a protective dose of sulfur to their expensive investments as soon as possible to inhibit any spoilage bacteria and reduce the effects of oxidation. Since they can’t do that until both alcoholic and malolactic fermentation is complete, it has become a common practice to co-inoculate for alcoholic fermentation and MLF at the same time, or no later than a week or so apart. That way, come the onset of winter, all the good and necessary microbial action is complete and the wine can been tucked in with a sulfur nightcap, and put to bed for a long, safe nap.

All this I learned in my Wine Production class about a month after all my wines—my expensive investments!—had finished fermentation and were racked into their individual barrels without me having inoculated for MLF. Aaugh!

So now what? I definitely wanted my wines to go through MLF, but I also wanted to get them protected for the next thirteen or fourteen months they were going to be in the barrel. And it was getting colder at night, and the odds of spontaneous MLF getting started and completed before winter came were slim. As I look back on it now I realize how little I had even considered the problem. Why hadn’t I thought about inoculating for MLF? Another classic home-winemaking faux pas on my part.

I voiced my concern, and barely camouflaged shame, to a real winemaker I knew, and he surprised me with his answer: “I don’t know, dude. All of my wines were through MLF within a month after fermentation. Nope, didn’t inoculate. It just happened. Yours are probably finished too”

What? Well… gee, I hadn’t even considered that. I then posed the question to Jack, who owns and runs Magnolia Wine Services, the custom crush I’m using, and where my wine lives. “Yeah, we don’t normally inoculate for MLF, as everything here in the winery seems to just go through it on its own.”

Hmmm. All of my barrels were once-used French oak from a celebrated Cabernet Sauvignon winery in Napa, so yeah, they surely have held wine through MLF and probably still harbored bacteria deep in the wood. But I’ve got an additional 135 gallons of wine that went straight into new steel kegs. Can’t imagine any of that has gone through MLF.

There were two ways to find out:

1) I could send wine samples into the lab at $30 a pop and have them run a malic acid and lactic acid grams-per-liter analysis. If the malic acid was really low or non-extant, and lactic acid was now present, well then, the wine has probably gone through MLF.

2) I could resort to a little high-school science-fair chemistry and run a paper chromatography acid test on all my wines.

The decision was easy. Chromatography was just too cool and to colorful, with just the right amount of science geekery, to pass up, so I quickly ordered a chromatography test kit from morewinemaking.com. At $99 it wasn’t a whole lot cheaper than the lab analysis would have been, but the kit is good for at least 25 tests of up to six samples each, and you can replace individual components when they run out. So yeah, definite money saver.

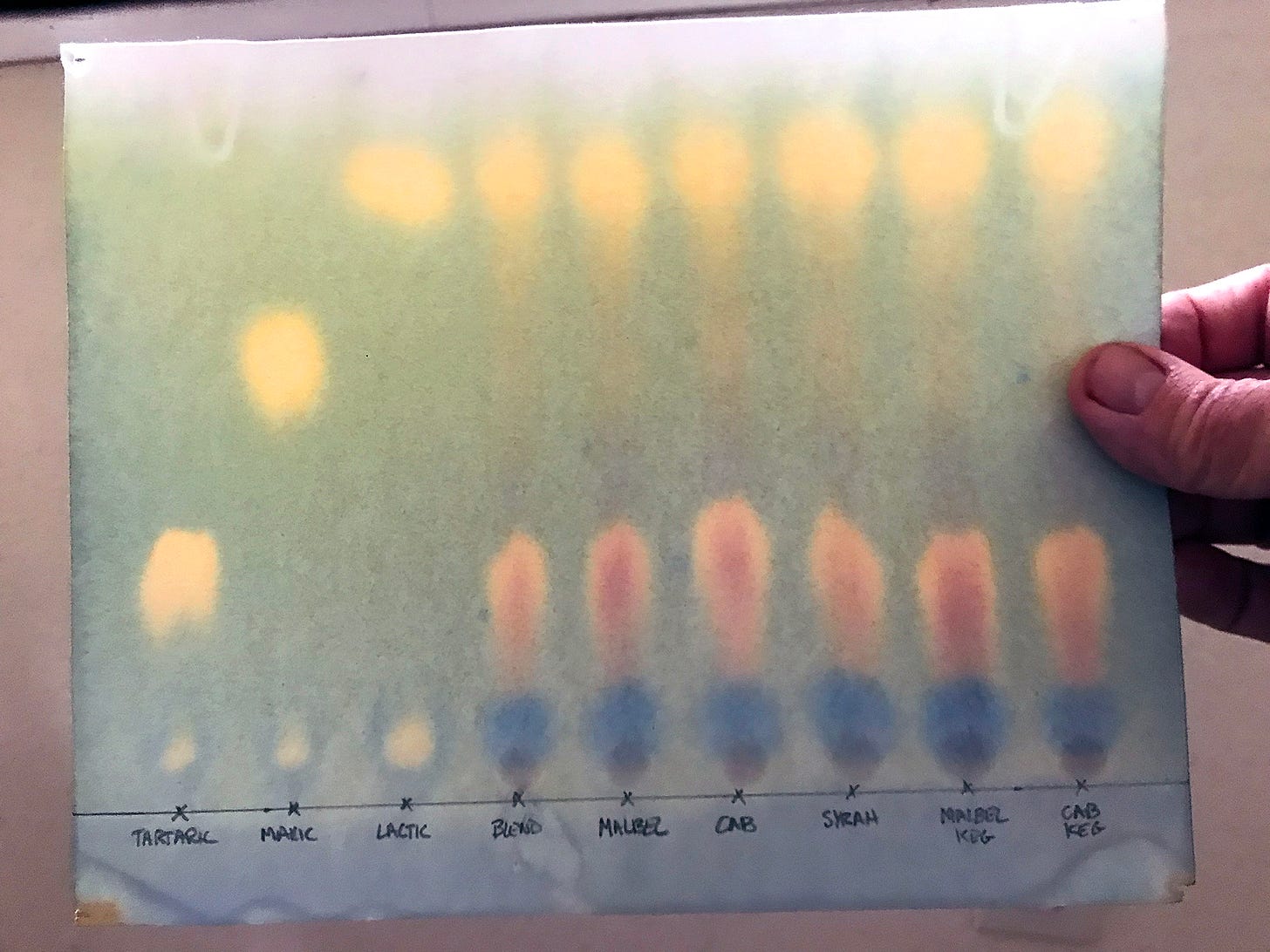

The process is pretty easy. Just draw a pencil line an inch up from the long edge of a sheet of chromatography paper and mark an X every inch or so along the line. Next, label the Xs from the left, first with the acid standards and then with whatever wine samples you want to test—in my case that was Blend, Malbec, Cab, Syrah, Malbec Keg, Cab Keg.

Then, using the pipettes, put a drop of the appropriate acid solution above each of the first three Xs and a drop of the appropriate wine sample above each of the remaining Xs, and let everything dry.