Anni, amori e bicchieri di vino, nun se contano mai. An Italian proverb that translates to: Years, lovers and glasses of wine; these things must not be counted.

Perhaps the most challenging wine I’ve ever made

Early this past Monday the mobile bottling line we use—ensconced in a full-size semi truck that backs up entirely into the winery—turned on its conveyor belt and began filling clear flint bottles with a light honey-colored nectar that has been the lifeblood of the northern Mediterranean for centuries. Each bottle then received a shot of inert gas to replace any oxygen lingering in the neck, and was summarily sealed with a “technical” composite cork, spun with a gold capsule, and labeled with my repurposed Daniel’s Pride brand logo—a mark harboring a significant, albeit shorter history of its own.

The emotion I felt (and as melodramatic as that may sound, there surely was some) as those fully-dressed bottles of Daniel’s Pride Vermentino were plucked from the end of the conveyer belt, packed 12 to a case and stacked on a pallet, welled up from more than one source. This wine had been damn hard to make. Scary, actually.

I first tasted Vermentino the way most people do, on a trip to Italy. As I write on the back label of the Vermentino I would subsequently make, “Order a glass of wine at a rural trattoria in Italy and it’s likely your only options will be a local red or white. And, if you’re in or near Tuscany, Sardinia, or Liguria, it’s also likely that the white wine is going to be Vermentino, a delicious varietal in the style of Sauvignon Blanc—crisp and dry, with bright acidity and minerality, aromas of pear and peach, and notes of grapefruit, lime and almond.”

What can’t be as easily expressed is the sheer delight the wine imbues. It is a perfect white wine, light but terrifically complex, and absent the heaviness of Chardonnay, the fruit bowl of Sauvignon Blanc, the sweetness of Riesling or the frugality of Pinot Grigio. And yet, it smells like flowers. Yep, actual flowers. Like you plunged your nose into a bouquet of wild blossoms. I guess that is what is meant by the wine descriptor “floral,” although I’ve never really smelled “that.” Until now.

You can, and will, drink Vermentino unencumbered. But to pair it with bean soups, light pastas, or grilled fish is to release the angels.

From my first taste of Vermentino in September of 2023 at a seaside cafe in Cinque Terre along the Mediterranean coast high on the boot of Italy, I was smitten. So much so that I vowed to try and make it during my very next vintage. And so I did.

Finding Vermentino grapes in California that would give me the authentic Italian taste I craved was challenging in the way that finding authentic Mexican food is in a northern city. I located a modestly priced vineyard down in Paso Robles, but it’s too hot there, more conducive to devils than to angels. I sussed out an overly-priced vineyard up in Dry Creek, but why pay so much for terroir so different from the perennial sun-bathed days and ancient rock of the Mediterranean.

Soil born of decomposing granite was what I was after. And what is more granite than the Sierra, more decomposing than the foothills? Hey, there’s an AVA named that! All I had to do was turn around and look eastward. I cross-referenced decomposing granite with Vermentino, with days of sunshine and cool nights, and came up with the unheralded Sierra Foothills AVA in slightly more heralded Amador County. And there I found a vineyard that seemed perfect, and it was perfect… except when it wasn’t.

That I had to rent a trailer with a one-ton payload, and a truck to tow it… That I had to drive over 100 miles in the nightly commuter traffic of Sacramento to the tiny hamlet of Plymouth, and spend the night at a hotel that advertised only “one room left” but in reality I was the only guest… That I would have to get up at zero-dark-thirty the next morning, find the vineyard in the pre-dawn darkness and load my trailer with 2,300 pounds of grapes, before merging into the same commuter traffic that was now headed back in the direction of San Francisco at a white knuckle pace… These were just inconveniences. In reality it was a lot of fun. Not an efficient or inexpensive way to source grapes, but an adventure nonetheless. And I had an amazing dinner that evening I arrived in Plymouth at a restaurant unapologetically named “Taste.” Grilled hangar steak, roasted vegetables, and a local bottle of— you guessed it—Vermentino!

Arriving safely back in Sonoma after several hours of high-speed highway roulette with yet another overloaded trailer of grapes—do I ever feel like I’m pushing my luck? Is it tempting fate to even write about that? Anyway, back home in one piece with fruit still cold from the pre-dawn harvest, I do a little dance. Shoeless. On top of each half-ton container of grapes. This light pigeage (foot-trodding) improves the yield of whole cluster pressing and helps start fermentation.

Vermentino is usually made in steel tanks, rarely in oak. Some winemakers, though, allow it to go through malolactic fermentation, which produces a creamier medium-bodied wine. But I was after that authentic Italian expression—light-bodied, complex yet refreshing—that relies on the wine’s natural high acidity, a characteristic that usually diminishes very little during fermentation.

Everything was falling into place. The vineyard owner had been terrific, more than fair about the price and happy to please. The grapes had been hand-picked in the cool night air, kept cold on the transport back to Sonoma, successfully full-cluster pressed at gentle fractions to an acceptable yield and skin contact, then pumped into an 800-liter tank and left to cool down further while a juice sample was taken and sent to the lab.

And that’s where everything suddenly went awry.

Here’s how I described it when I texted the vineyard owner a couple of days later: (Parenthetical comments in bold are inserted to help reader understanding.)

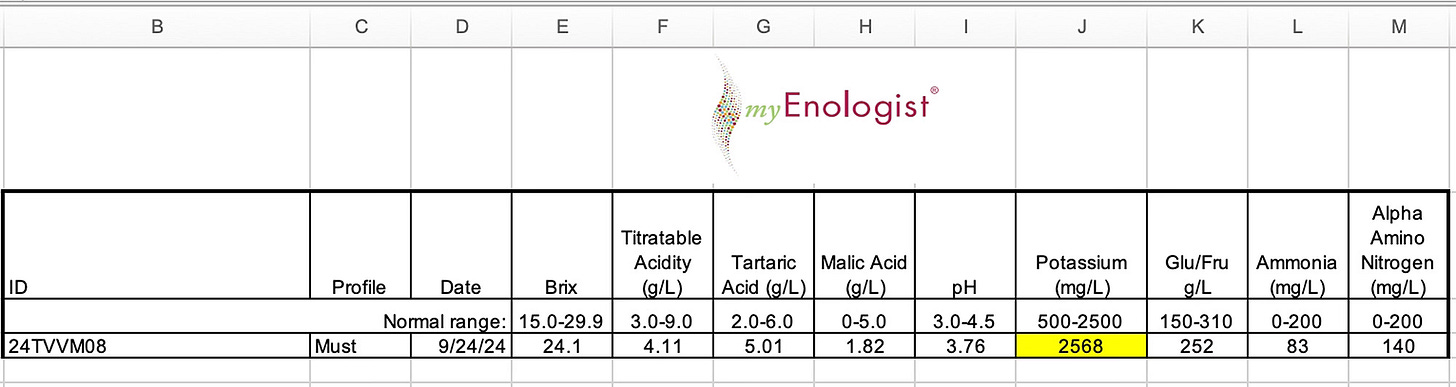

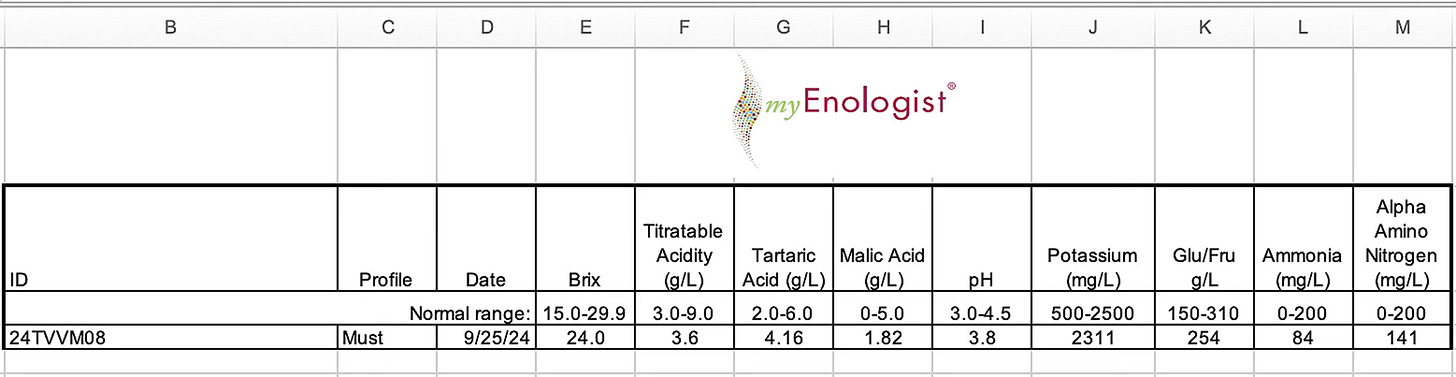

“Hey there, I might have a problem with your grapes. I sent you a lab report (above, top) a few texts back that showed you had excess Potassium (K+) in the grapes. This can be a real problem at times as excess Potassium causes the grape ‘must’ (in the case of white wine, just juice) pH to rise dramatically in the first few days of fermentation because of precipitation (loss of a compound from it coming out of solution) of tartaric acid and other free acids. This increase of must pH past suitable levels as Potassium binds with the tartaric acids reduces TA (Titratable Acidity, that wonderful zing that makes the wine refreshing) and you end up with a real flabby wine. I did another lab sample on the 25th (above, bottom) and that was exactly what was happening. pH had risen from an already high 3.76 to 3.8 (pH is exponential so even an increase of a few hundredths of a point is substantial), TA had dropped from an already very low 4.1 to 3.6, but Potassium had actually dropped from 2568 mg/L to 2311 mg/L. And fermentation had not yet begun, so I don’t know how volatile this is/might become. I immediately dosed the must with 2g/L (4 kg!) of tartaric acid and cooled everything down to 56 degrees. Now we’ll just have to let it ferment slowly and see what happens. Sorry my friend. Fingers crossed.”

The vineyard owner’s response, “No one else is having a problem.”

My comeback, “I can’t speak for anyone else or any other varietal, but Potassium is something that comes from the vineyard (fertilizer) as you know, and the chemistry doesn’t lie. Who else has picked Vermentino and what were their labs? And has anyone taken your Vermentino through fermentation yet this year? It might work out just fine. I won’t know for a couple of weeks or so. I’m just alerting you to the possible issue.”

No further comment from the vineyard owner.

I was flying by the seat of my pants, and I knew it. This was territory I’d never been in, and frankly, I couldn’t find anyone that had. I was truly worried that I was about to pour 150 gallons of very flat grape juice right down the proverbial, and literal, drain. I had one chance to correct the problem and I wasn’t sure my solution would even work.

The bottom line—in plain speak—was that the vineyard soil had an excess of Potassium, probably from too much fertilizer. The vine uptake of that Potassium had resulted in levels considered too high in the juice pressed from the grapes. That created a chemical reaction which caused the Vermentino’s normally high acidity to plunge by precipitating out of solution with the excess Potassium. That, in turn, caused the pH to rise and created an unstable wine. I could only guess that a Hail Mary addition of tartaric acid, administered at just the right time, might rescue the wine from a flabby future, and save the world.

Oh man, this was starting to feel like a really bad science fiction movie.

Cue the ominous music. Camera slowly zooms in on my anguished face as I cry out to the wine gods…

“But has enough Potassium precipitated out to end the chemical reaction that stole the tartaric acid in the first place?”

“And if so, how much tartaric acid should I add? Too much and everything goes sour. Too little and we’re right back to where we started from.”

Music fades out. Camera fades to black. A few moments of silence, nothing on the screen, then suddenly…

Orchestral strings swell into a celebratory sound of music, bringing to mind a nanny and her brood of cherub children running through the wildflowers of a meadow high in the Alps.

Camera pulls away from me smiling and toasting the world with a glass of honey-colored wine.

“Not only was the world saved, but it was made better with 65 cases of—and I’ll say it again—the perfect white wine. By the time fermentation had finished and the wine was safely bottled, the pH was down to 3.31 and TA was back up to 5.68 — perfect numbers!”

THE END

Vermentino is meant to be enjoyed while it is fresh and young. I started drinking it one day after it was bottled and I am a better man! Join me in toasting to life and simple pleasures (well, not so damn simple), and stock up on enough Vermentino to keep the angels at your table.

Get yours right now while this small, magical lot lasts at tinyvineyards.com