PLEASE NOTE: Part 1 of The Grapes Are in the House! was posted here two days ago. Part 2 was posted here yesterday. Now, for the rest of the story…

September 26 - Those never-ending things to do

We suddenly found ourselves with three days free. Head to the beach? Hardly. This was precious time to complete certain winemaking tasks that kept getting moved back. Like bottling—my least favorite chore. We had 40 cases worth of wine from 2021 in my little winery that needed to get into glass or we’d be running out of barrels and kegs and floor space before the season ended.

Deb is the absolute best at bottling, an indispensable skill she probably wishes she didn’t possess. But the only way to get it done is nose to the grindstone and she led the way, keeping us all on point until our 480 bottles had been corked.

And then there is the need for yet more barrels. While we might be suffering some yield issues when it comes to tons picked, the juice we’ve been able to extract from those tons has been much more than expected. Normally, a ton of grapes yields about two barrels worth of wine, plus a keg for topping off. So far, we’ve been averaging 30 to 40 percent more than that.

That’s a true bonus to be sure, but it’s also had me going back to my barrel source more than once already. It certainly helps that he’s the owner of a premium Napa vineyard/winery, and has for some unimaginable reason taken a shine to the Tiny Vineyards Wine Company mission. A heartfelt shout out to Wes!

September 29 - Syrah harvest for commercial wine

This morning was exquisite, a reason for why I got into all of this in the first place. Crisp, clear skies, colors so saturated they seduce the eye, and a vineyard fecund with fruit. There’s an ethereal quality to the air that elevates simple breathing to a sensual experience.

We’re harvesting Avram’s Syrah vineyard, or I should say Daisy Hernandez’s crew is harvesting Avram’s vineyard. Yep, she saved my butt again. Daisy, of Grape Land Vineyard Management, came up with the labor I needed on the day I wanted without any drama, just a “Yeah, we can do it.”

I could get used to this.

Avram’s vineyard has weathered the weather better than a lot of the vineyards I’ve seen, but it’s now right on the edge and I worry that the grapes could collapse if left on the vines any longer. The Brix is at 23° and hasn’t moved in weeks, but the acid is falling. Was there latent damage done by the heat dome and subsequent deluge rainstorm that’s simply too much for the grapes to recover from? I first described this to my grape guru Ken Wornick as tantamount to radiation sickness. He liked the analogy and ran with it. Whatever it is, it’s seemed to put the brakes on grapes ripening any further than they were before Mother Nature had her little hissy fit.

Daisy’s partner, Marcelo, Daisy, and I had walked the vineyard earlier and I had allowed as to how we might get upwards of two tons of Syrah. Marcelo thought maybe a bit more. “Bring five bins, just to be safe.”

Estimating vineyard yields has to be one of the most difficult guessing games out there—for everyone, regardless of experience—and we proved our ineptitude yet again when the pick came it at only 2,292 pounds—a little over 1.1 tons. “Dammit, here we go again,” I thought out loud. I had counted on at least a ton and a half, just to keep our 10 tons target in sight.

Now what?

October 1 - Pressing Aerie Cab and Brad’s Cab

Our mountaintop Cabernet Sauvignon—which is called Aerie—took over three weeks to ferment, which is not surprising given that it started at a Brix of 28.6°. It got down to 10° within the first week and then took the next 15 days to go dry. I nursed it along by adding some yeast hulls about halfway through when it started to stumble.

Brad’s Cab took less than two weeks, which put them both ready to press on exactly the same day. The aerie Cab was big, very Cabby, and very alcoholic. Brad’s Cab was reserved, so much so that I’m not sure I would have identified it as a Cab. Should I be worried, given this is our pièce de résistance? At least we paid for it as if it was.

If I’ve learned anything in five years of winemaking it’s WAIT. Nothing is ever as it seems. A year or more in the barrel and a year in the bottle, then you can start freaking out if your prized Cabernet Sauvignon is tasting more like Two Buck Chuck.

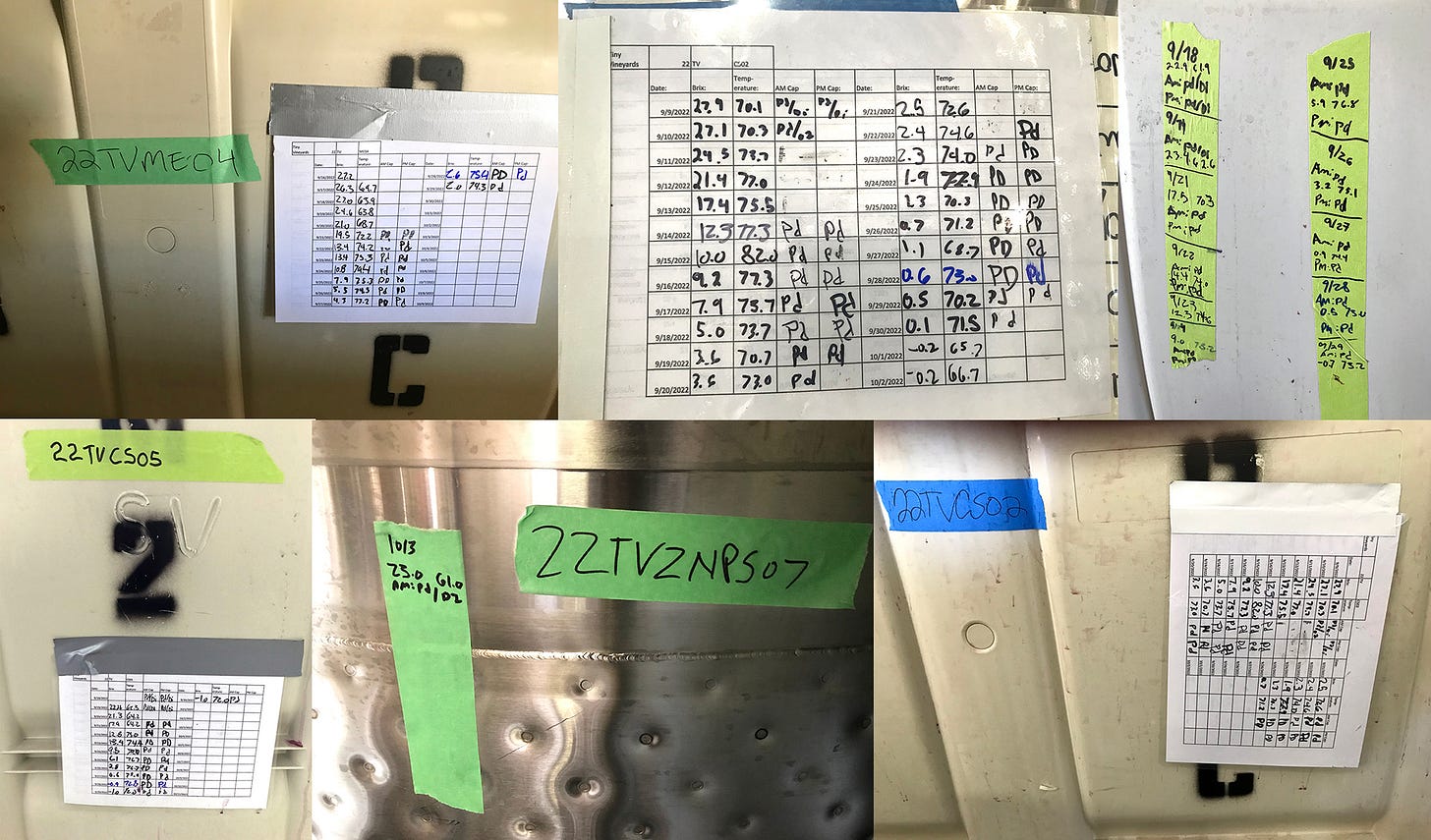

There’s a system at Magnolia that ensures that wines don’t get accidentally mixed up when they’re being processed. The moment a bin of grapes comes into the winery, and is weighed, a piece of colored tape is slapped onto that bin with a simple code identifying who it belongs to and what it is. The Aerie Cab was 22TVCS02. That means it’s a 2022 vintage — belonging to Tiny Vineyards — of Cabernet Sauvignon — and it’s the second lot brought in that year. Brad’s Cab was 22TVCS05, meaning 2022 vintage — belonging to Tiny Vineyards — of Cabernet Sauvignon, 5th lot of the year.

That piece of tape and whatever fermentation sheet or other record of production follows that particular wine, getting affixed to whatever container is being used as it goes through crushing and destemming, cold soaking and fermentation, pressing, settling tank, and ultimately barrel. It’s a pretty good system and it’s fairly fool proof—until it isn’t.

As I was waiting my turn on the press, I walked past my fermentation bins that had been queued up in the order they would be processed. Just barely, and by the luck of a second glance I noticed that the bin containing Brad’s Cab was followed in line by a bin of my Merlot instead of the second bin of Brad’s Cab. Whoa! Stop the presses! (Ha, funny how that saying really works here).

I immediately alerted Jack—Magnolia’s boss man—who was loading the press with my Aerie Cab. He, in turn, immediately called out (very nicely, but firmly) the poor cellar rat (an affectionate term bestowed on the cellar crew members) who had staged the bins. Embarrassment was shared by all, the correct second bin of Brad’s Cab was put in place of my Merlot, and disaster was averted.

October 3 - Zinfandel, Petite Sirah and Mourvèdre harvests for commercial wine, plus more Cabernet Sauvignon

For the last four years I’ve made a red blend that consists of proprietary amounts of Zinfandel, Petite Sirah (Durif, outside America), Syrah, and Cabernet. The first three years that blend won two Silver Medals, two Gold Medals, and a Best in Class in the two largest amateur winemaking competitions in the country. The fourth year, my first commercial vintage, is yet to be determined.

I planned to make it again this year and was able to source a new Zinfandel/Petite Syrah field blend (which is how I’ve always made it) that would allow me to give it a Sonoma Valley AVA designation. It was an interesting deal, a private vineyard planted in two blocks—Petite Sirah and one clone of Zinfandel in the backyard, and a different clone of Zinfandel planted in the front yard. There were enough vines in total to produce about 1.5 tons of grapes, or three barrels.

The owners had made wine themselves from the vineyard for the past few years but this year were considering something different. I had met them a year before when they were seeking some guidance on pruning and I’d stayed in touch. This past summer we started talking about options and finally hammered out a deal where they would give me the ton of field blend I needed in return for me making them a barrel of wine from whatever grapes were left over. It sounded great, and by the end of the summer it was apparent there would be enough grapes to fulfill everyone’s need.

That was the case, until it began to get hot.

The heat dome did its invisible damage and the two inches of rain that fell a week later seemed to mask the carnage, plumping the grapes up to marble size. The only problem was that the Brix was seemingly locked at 21°, when I was looking for 25° or 26°. Then suddenly, many of the grapes on the south side of the rows, particularly amongst the Zin in the front yard, started to collapse and shrivel. Specks of white mold could be seen, and there was evidence of bunch rot or maybe even Botrytis.

I convened a quick pow wow with the owners and explained that I was no longer sure there would be enough grapes to make my ton of wine and their barrel. And if we waited too much longer neither of us would even want the grapes. They were pretty adamant that they get a barrel of wine out of the deal—which I fully agreed was how it should be—but they said that I could make it from other fruit I might have, or could source, as long as it contained at least some of their grapes.

So that was now the mission. I called Daisy and arranged for a picking crew as soon as possible. Two mornings later I met the crew at the vineyard and we picked every usable grape we could. That required a lot of hand sorting and the rejection of many bad clusters, and we ended with just a little over a ton (see video above).

I remembered to hold back about 10 buckets of the grapes for the owner’s barrel of wine. Then I called Deb, who was picking 10 more buckets of Cabernet Sauvignon with Tom that we could use to help supplement that barrel. “Hey, can you guys head over to Avram’s when you’re finished and start picking the Mourvèdre? I have an idea.”

You might recall, in the first installment of this harvest report, that I mentioned contracting for Avram’s entire vineyard in order to get all of his Syrah. That left a couple of small blocks of Tannat and Mourvèdre. We processed the Tannat with the Primitivo we picked, but the Mourvèdre had been kind of a lost child. Suddenly I realized it might be just the thing to boost and brighten our Zin/PS blend that had suffered so badly. Into the hopper with everything!

October 10 - Grenache and Syrah field blend harvest for personal/client wine

I’ve got this crazy little vineyard I’ve been farming that really isn’t even a vineyard. It’s a single row that winds around the perimeter of a pretty big lot up on Sonoma Mountain off of Bennet Valley Road. New owners have bought the place and refurbished the house as an AirB&B. Casa Sol they’re calling it.

They’ve asked me to restore the “vineyard” by replanting over a hundred dead or missing vines and rejuvenating the old Grenache and Syrah vines that are still alive and standing. They also asked me to make them some wine from those existing vines so they could give it to their AirB&B guests and business associates.

The only problem is that the vineyard is wildly out of balance with the Syrah ripening weeks before the Grenache, and neither one of them in enough volume to bother with making two different lots. This left us wondering what to do as the birds started figuring out the bird netting (that Tom had gamely installed) on the overly sweet Syrah, and bees and hornets simply flew through the webbing and gathered en masse. Meanwhile the Grenache sat relatively unscathed with lower sugars.

Then a light bulb appeared over my head in one of those caption balloons you see in the comics. “Here’s an idea. Make Rosé!”

“Heck yeah!” I replied in the next frame. And so we did, rounding out our winemaking exploits of 2022 to include just about everything.

October 13 - Malbec harvest for commercial wine

Ah, Malbec… My muse, my sorceress. We are going to talk further about my infatuation with Malbec in a future post. Just suffice it to say, for now, that I am on a quest to find grapes in California that can make wine that tastes like it came from Argentina. That search has led me to a vineyard just outside Sonoma, one up in Dry Creek, another in Bennet Valley, and this year I’ve strayed the furthest yet from home, to a vineyard named Bells Echo in the Mendocino highlands above Hopland.

I found Bells Echo during one of my frequent perusals of the grapes and bulk wine classifieds on winebusiness.com. You don’t see a whole lot of Northern California Malbec advertised there, but what really caught my eye was the ad’s mention that the grapes were from Clone 9 vines (considered by many oenophiles to make the best Malbec), and wines made from them had won a few awards. The bad news was they were selling grapes in bulk-size lots. I didn’t know how they’d respond to someone wanting to buy only one ton.

The fact is, they didn’t respond at all. Which was disappointing because I had sent them this long diatribe on my passion for Malbec, my desire to make California’s finest, and my “poor, struggling, almost 70-year-old winemaker” saga. I thought that would clinch the deal! I waited several days and then responded again. I even left a couple of messages on two phone numbers I found. Still no answer.

In the meantime, I had sleuthed out where the vineyard was (the ads don’t tell you) and decided to drive the two hours north to check it out. I found it easily enough, and the gate was even open. But no one was around—anywhere. After driving all around the place long enough to start feeling like a bona fide trespasser, I left. But not before writing them a letter on a page torn out of my notebook and stuffed into their roadside mailbox. I couldn’t think of anything more I could do.

A long two weeks later I finally received an email from a Ron Sutton apologizing for his slow response and explaining that he’d been back East getting his daughter situated in her first year of college—Rhode Island School of Design (where my daughter had also gone). Aha, a connection!

After answering a bunch of questions I had sent him earlier about logistics, on the off chance that he might find it in his heart to sell me a ton of grapes, he went on to write, “We typically do not sell small lots like one ton! But we like your story! If you are still interested we can get you one ton.”

Bingo!

Ron and I would go on to establish a genuine connection (I least I felt like we did), and I drove up there again to meet him and check out the grapes. We eventually ended up at the Northern end of a block of Clone 9 that was beautiful. “This is where my wife told me to bring you in the first place. Malbec is her favorite wine, and she thinks the best grapes come from here.” I couldn’t argue with that.

“The block starts with row thirteen…”

“Wait, that’s perfect,” I interrupted. “Thirteen is my lucky number.”

“Yeah, mine too.”

That sealed the deal. Nothing more was said about the number thirteen, except it turned out, purely by happenstance (or was it?), that our eventual harvest date—when all the chemistry was right and there was a picking crew available to pick my ton, and ten more tons for another client—was October 13. I’m just saying…

By the time that lucky day arrived I had upped my order to a ton and a half. This was my final pick of the season and it was the only way I was going to make my 10-ton quota and collect the Magnolia discount. But the problem with 1.5 tons is that it was stretching the working load of my rental trailer by a lot, not to mention my Subaru Outback, which I treated unapologetically like a truck. What with the trailer weight, the bins and the grapes I was approaching 4,500 pounds. At least my trailer hitch and ball were rated for that, just barely. I honestly had nightmares the night before of major trailer malfunction and grapes spilling onto the highway at 60 mph.

I finally left Bells Echo at about 10 mph. By the time I had driven the farm road back to Hopland I was doing 30 mph. I had worked myself up to highway speed by Santa Rosa, but it wasn’t until I pulled up in front of Magnolia that I quit holding my breath!

Cellar magic and mayhem

It always blows me away when I think about the amount of time and effort that goes into making wine. Sure, I can hear your tiny violin playing right now as you guffaw, and think to yourself that it’s only for a couple of months each year, slacker, and then you can retire to the couch. And that’s pretty much true beyond the monthly maintenance one must conduct on barrels aging in the cellar. Oh wait a minute. I forgot the marketing and sales you have to do 24/7 during the other ten months just to get rid of your juice. But never you mind.

And it is true that even during the harvest you’re not always doing a big pick or a critical press every single day (although it certainly feels that way sometimes). Yet the fact remains that you are generally doing something, always—from sampling grapes and coordinating harvests early in the season, to punch downs twice a day, along with temperature checks and Brix measurements as the lots go through fermentation. And in the spirit of keeping it real, the winemaker isn’t the muscle that gets everything done. The hard tasks fall to the cellar crew.

Punch downs are where the one-to-two-foot-thick cap of crushed grapes that forms on top of the fermenting juice each night needs to be “punched” back down into the wine twice a day—every day—during its two to three weeks of fermentation in order to encourage extraction and prohibit microbial spoilage. This cap can be as hard and immovable as packed dirt, and the task is very physical.

With Magnolia processing over 180 tons of grapes a season, that could translate to more than 5,000 punch downs for our crew of five, all operating under the truly exemplary leadership of co-owner Jack Sporer. That on top of their myriad other chores, from pulling hoses to cleaning tanks to sanitizing every piece of equipment to endlessly moving things about. My hat is off to everyone. I simply couldn’t make wine at this scale without them.

Things are a bit different at my little backyard winery where I’m not only el jefe, but also quite literally the chief bottle washer. And it is here that I encountered my most vexing problem of the season—a dreaded stuck fermentation.

Other than for my Chardonnay, my Rosé, and a couple of forays into going native, I pretty much stuck with one yeast this season—BDX from Uvaferm. This is a very reliable fermenter for structured reds, which is what I make. Using it for ten different lots of grapes, from 21° Brix to 29° Brix, I got them all through to negative Brix dryness, except one—that tiny lot of exceptional old-vine Zinfandel which, yep, was probably picked a bit too late.

As you may recall from Part 1 of this harvest report, we picked that Zin at 28° Brix on September 13th, three days after the heat dome. It had a pretty normal fermentation curve until around the end of September when it started to stall at around 9° Brix. I had given it a normal dose of nutrients in the form of Fermaid O a week earlier and so decided to nourish it further with some yeast hulls. That perked it up again and the Brix dropped to 7° over the next week before stalling again.

Then on October 8th I started Scott Lab’s protocol for reversing a stuck fermentation. I tried it first on the must with only modest success, so I pressed off the wine and continued the protocol. This got it down to around 4° Brix over the next two weeks, but then it locked up and wouldn’t move a fraction of a degree, despite additional rackings, nutrient doses, moving it outside into the warm sun during the day and keeping a space heater going in the winery at night.

On October 23rd I split the wine up into a 7-gallon Italian glass carboy and a 15-gallon Hungarian oak barrel. My intention was to make port from the wine in the carboy—which had been agreed to by the vineyard owners—and to try one more time to restart the alcoholic fermentation with the wine in the barrel.

I ran through the entire stuck fermentation protocol again with the wine in the barrel, a process with 18 steps that took over three days. Then I put a water-filled airlock on the barrel, warmed the temperature up to the low 70s and kept it there. And damn if that airlock didn’t start to burp after a few days. And it’s still burping—I checked it today—our 46th day of fermentation! But I’m not going to pull out my hydrometer to see where the Brix is until that airlock has been totally still for a couple of days. Otherwise, it becomes a chore just as futile as watching the clock.

I did, however, taste the wine today. It is delicious and noticeably less sweet, with no signs of oxidation or microbial mischief. So, there’s hope yet. The special kind of hope that springs eternal in fisherman and winemakers.

October 31 - Cheers to you!

That’s the story of my 2022 harvest. It may be way too much for some folks, but for me it was an amazing time. We pressed and barreled that magical Malbec a couple of days ago and that ends my big harvest events—at least until a month or so from now when everything has gone through malolactic fermentation and we can stage all 26 barrels of 2022 vintage wine to rack and sulfur them, and put them properly to bed for a long winter nap.