Vintage Number Two

A winery of my own, Bobbie eats cake, and a label is denied

Occasionally I have a glass of red wine. I don’t consider it an alcoholic drink. I consider it a holy drink, something that can also be used as a curative. – Novak Djokovic, tennis champion

I’d rather eat pasta and drink wine than be a size zero. Everything you see I owe to spaghetti…and vino. – Sophia Loren

A slippery slope

My second vintage in 2019 brings to mind that old proverb—out of the frying pan and into the fire—about the dangers of a growing obsession and overt involvement. Only in my case, out of the laundry room and into the garage might be more accurate. I went from making just ten gallons of wine the year before to over 60 gallons my second year.

And I bought a real wine barrel—not a harsh American-oak whiskey barrel like the one I had effectively used to over-oak my first batch of wine, but a beautiful, brand-new French-oak barrel that cost a boatload of money. Sure, it was a 30-gallon one instead of the normal 60-gallon, but those cost a shipload of money and I was still a little intimidated at the thought of making 60 gallons of anything.

But my barrel was the genuine thing, a simple design centuries old with beautifully planed staves on the outside and a special medium-long toast inside—guaranteed to deliver the same relative amount of oak extraction to my 30 gallons of wine as a standard barrel would to 60 gallons of wine. It was a piece of art with its galvanized iron bands and Tonnellerie’s (cooperage) brand—Saint Martin— burned into the head. I literally hugged it when it arrived and vowed fidelity to Saint Martin for the rest of my life. I’m not sure if I’ve ever had a crush on an inanimate object before, but I was definitely in love.

Should I be worried about this?

Harvest

My plan was to make two wines, 30 gallons of Cabernet Sauvignon from Sam’s Vineyard (where I had picked 70 pounds of grapes the year before), and 30 gallons of a specific red blend—not the pick-whatever-is-left-from-whatever-vineyard-will-let-me approach I had employed in 2018.

The Cabernet Sauvignon was easy, or so I thought. I needed about 750 pounds to make my single-varietal 30-gallon barrel and supply my red blend with the percentage of Cab it required. My friend Sal Troia was managing Sam’s Vineyard at the time and was charged with selling as much of the crop as possible. It was a glut year in grape production and there weren’t too many buyers to be found, although he said he had a couple of potential buyers lined up. Since I had never bought a grape in my life I had no real idea what they might be worth. You hear those outrageous stories of a ton of grapes going for $10,000 from the premium Cab vineyards in Napa. But this was a front-yard hobby vineyard in Sonoma.

I offered Sal fifty cents a pound ($1,000 a ton) and it took almost two months of heavy negotiating to get him to finally accept my price. And then I think it was only because one of his other buyers fell through and he decided to take pity on me. Whatever it was, Sal, I’m still very appreciative!

The other varietals I needed to complete my red blend didn’t come any cheaper. Winemaking maestro Ken Wornick, of Dysfunctional Family Winery, came through (as he always does) with 250 pounds of Zinfandel and 150 pounds of another varietal from two of his clients’ vineyards on Norrbom Road in Sonoma and Hoff Road in Kenwood, respectively. But the clients each wanted $1.05 a pound. Then I had to find 100 pounds of Syrah to round out the blend—which I did, from Bruce Russell’s vineyard high atop a mountain on Westside Road outside of Healdsburg. Bruce makes a fine Syrah under his own label, which you can also buy at Whole Foods. His price for grapes was $1.25 a pound. When you’re buying such small quantities you don’t have a lot of bargaining power, so I just dug deeper into my pocket.

Honoring the blend

I wrote about my 2019 Cabernet in an earlier post, but it’s my blend that has given me both sweet dreams and nightmares ever since I took it on. My original idea was to find an inexpensive, everyday blend I really liked, deconstruct it (i.e. figure out the various components), and then make sort of a tribute vintage to honor the heritage of the original blend. That’s it! I’ll call it Heritage.

It took quite a bit of research—probably more than was necessary—to find the right wine, but I finally settled on Essential Red from Bogle, a large commercial winery in Clarksburg, California. You can find Essential Red in wine shops and grocery stores all across the country for as low as $8.99 a bottle. And it actually tastes pretty damn good for a sub-$10 bottle of wine. Bogle won Wine Enthusiast magazine’s Winery of the Year in 2019.

Tracking down the recipe for Essential Red took a little more effort but I finally found it—an ever-evolving combination of Cabernet, Zinfandel, Syrah and that grape which will go unspecified. C’mon, Coca-Cola doesn’t divulge their recipe! Just kidding, the four varietals used to make Essential Red are listed right on the bottle…but not the percentages. You have to dig to find that!

It was a blend worth working for, and driving all over Sonoma County to attain.

I had moved my winemaking operation out of Deb’s laundry room into Bobbie’s…er…laundry room. Only her laundry room was in her two-car garage, which had a lot more room despite being the parking pad for a beautiful vintage Harley Davidson scooter. Didn’t matter, as there was plenty of room—and excellent temperature controls—to ferment and barrel 30 gallons of Cabernet Sauvignon and 30 gallons of my new Heritage Red Blend. Besides, the move was only temporary. Bobbie had promised a 10’X10’ addition to her backyard garden shed as a new winery—and we were only weeks away from it being completed!

Bobbie is nothing if not fully engaged in the winemaking operation. She truly loves the whole concept. There’s a fun tradition in home winemaking that when you press your first basketful of grapes you have to take a bite of the “cake,” which is the compacted pomace (grape skins, seeds, occasional stems and leaves) that is left over after the must has been pressed dry. It really doesn’t taste as good as you might think, but Bobbie was all in, as you’ll see in the video below.

A new winery

One of the things I’ve grown to appreciate about Bobbie is that when she decides to do something—and it might take some time for her to make that decision—she fully commits and gets it done right. But when she started talking about extending her existing garden shed to make room for a little winery, I was dubious. I mean, garden sheds aren’t exactly prime examples of high-end construction, quite the opposite in fact. A winery has to be built to handle a lot of wear and tear—and weight! And it needs to be insulated, wired for electricity, and plumbed for water. It needs a big, secure door, lots of shelves, and adequate ventilation. Nope, that’s not a garden shed. But where I had an attitude Bobbie had vision, and it quickly became a pet project for her.

She hired Mike Ross, an elderly, retired contractor who was still an active musician, but didn’t swing a hammer too much anymore. I wasn’t sure he could even dig and pour the pylons or handle the heavy lumber needed to construct the floor and frame the wall and roof—especially by himself! But once again, I was wrong. He wasn’t fast, but he was strong, and damn good at his trade. And from the rear of Bobbie’s garden shed slowly emerged a ten-foot-square matching extension that was just perfect. Mike had a blast building it and remarked as to how it was one of the funner projects he had done in a long time.

Next, Bobbie enlisted Bob Jones, one of her gang of close friends, and an accomplished do-it-yourselfer. Bobbie relies on his talents for a variety of projects. Bob also manages the wine collection of a long-time collector in San Francisco and has unlimited access to those great wooden boxes in which most foreign and premium wines are shipped. As a final touch, Bobbie wanted to panel the back wall of the winery with the logo-stamped sides of the boxes, and Bob skillfully obliged.

The almost-birth of a great label

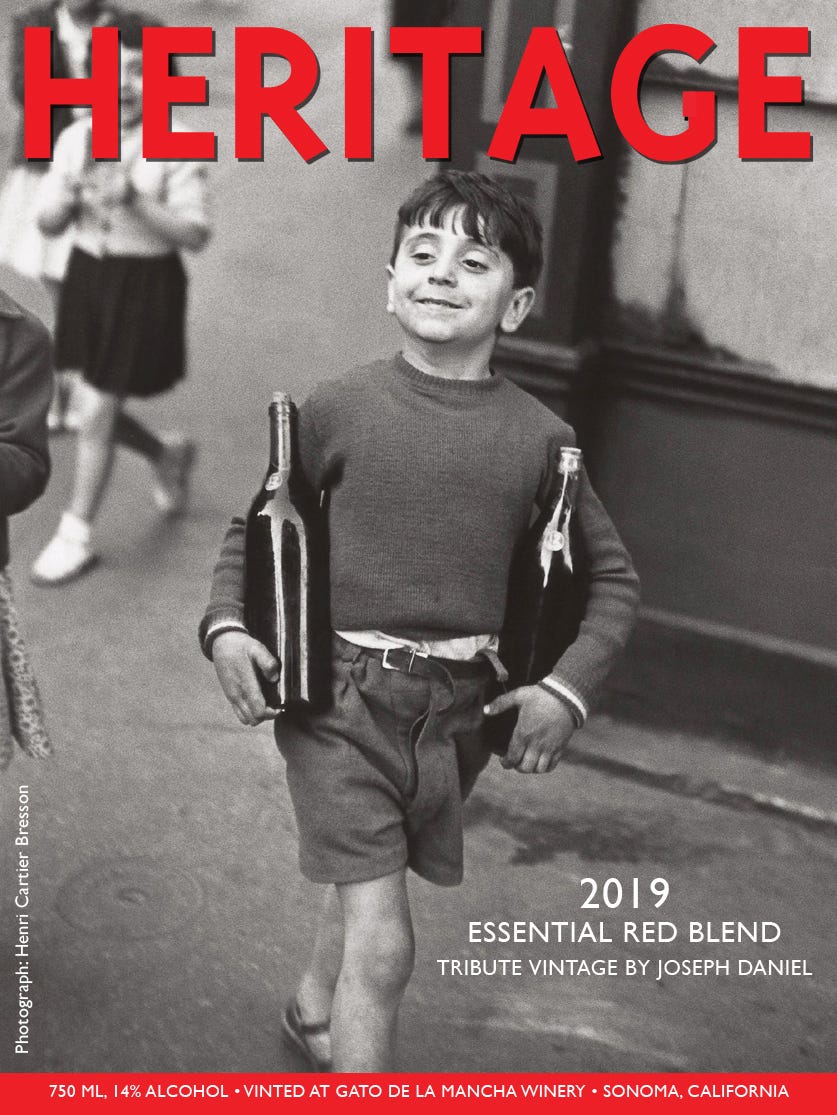

So, back to my 2019 vintage red blend. I did, in fact, end up calling it Heritage. And it actually did (and still does) taste quite a bit like Bogle’s Essential Red. I also found what I thought would be the perfect photo for the label—a black-and-white shot of a proud young French boy in Paris, presumably carrying home two bottles of wine for his family. The photograph was taken by Henri Cartier-Bresson in 1954 (the year I was born) and is simply titled Rue Mouffetard.

A quick distillation of Google searches reveals that Cartier-Bresson, born in France in 1908, “was a pioneer in photojournalism and helped to establish that style of photography as an art form. He wandered the globe and covered many of the world’s biggest events from the Spanish Civil War to the French uprisings in 1968. He was captured during World War II and detained as a prisoner of war for three years by the Nazis, prompting rumors he’d been killed. His photography was taken seriously enough at that point that the Museum of Modern Art in New York began preparing what it believed would be a posthumous retrospective of his work. But he was still very much alive, and after two failed attempts he finally succeeded in escaping. He immediately returned to his work as a photographer, and in 1947 he teamed up with Robert Capa, George Rodger, David Seymour, and William Vandivert, and founded Magnum Photos, one of the world's premier photo agencies.”

I myself have been a freelance photojournalist and filmmaker for most of my professional life—before winemaking began to steal away my passion—and I quite literally revered Cartier-Bresson. I truly wished (as I have on many occasions and for many reasons) that I had been born 50 years earlier so as to have had the opportunity to live the life he did, and apply my craft during the true heyday of print media and film photography, before the dawn of digital degradation, and as Pogo once put it, our “crisis of mediocrity.”

But there I go again. What happened with the label was this: I have used it for two years now on wines that I made as a home winemaker. I figured that was okay. They were only for me and my friends, and I wasn’t selling any of them. But I knew that if I wanted to use it going forward on my commercial wines that I planned to sell, I would have to get permission and properly license the image. And I also knew that was highly unlikely.

But what the hell, I might as well give it a shot. You never know until you ask. So I tracked down the person in charge of licensing at Magnum in New York and sent him the following email:

Dear Mr. Murphy,

I know this is probably a long shot, but I am a small, independent winemaker in Sonoma, California and every year I make a Heritage red wine blend in the spirit of the great Bordeauxs. I was a successful photojournalist for most of my professional career (still take an occasional assignment), and of course am very familiar with the great shooters who came before me.

Because of that, and because it is simply such a wonderful image and very emblematic of the small-lot winemaking that I do, I was wondering if there was any chance of obtaining permission to use one of Henri Cartier-Bresson's photographs on my wine label. I've mocked-up a label with the photo I wish to use and have attached it to this email for your review.

Thank you very much for your time and consideration.

All the best,

Joseph Daniel

Thirty-four minutes later I received the following response:

Dear Joseph,

In 2007, Cartier-Bresson's widow, fellow Magnum-photographer Martine Franck, permanently withdrew this image from circulation at the request of the subject (or the subject's family). That being said, we're unable to provide permission for any licensing use. I should also note that none of HCB's images could ever be used for commercial or advertising use. This was a rule he set while he was still living and which we continue to respect.

Interestingly, in or around 2007, it was discovered that a winemaker in Australia had used this image without permission and consequently, they were hit with a substantial lawsuit.

Sorry for the bad news.

Best,

Matt Murphy

Archive Director and Licensing Manager

Magnum Photos New York

So there you have it. A great anecdote that showed up when I was researching this newsletter was that the name of the boy carrying the wine in the photograph was Michel Gabriel, and when he grew up he kept in touch with Henri Cartier-Bresson. Supposedly the famous photographer, already in his eighties, turned up at Michel’s 50th birthday party with a bottle in each hand, imitating the then-boy’s pose and his proud expression in the photograph.

It looks like you have fallen into winemaking head first. We should trade a couple bottles.